I was pretty bearish on Mario Cristobal’s Oregon team heading into 2019. Justin Herbert never really convinced me he was elite, the offense seemed overly focused on running the ball behind the offensive line, and the strategy of building Oregon around the offensive line always struck me as a dubious method.

Every school is always at least somewhat captive to the recruiting region they find themselves in. The state of Oregon itself isn’t one of the first you’d chose if picking a home base from which to recruit champions. The population is about 4.2 million and it’s not particularly diverse, although a relatively high number of Polynesians call the state home. From 2015-2020 the state produced an average of two blue chip prospects a year per 247. The Ducks also share the state and its recruiting with Oregon State and any good Oregon players that emerge will also have the attention of neighboring Washington and Washington State.

Here are the metro populations within a five hour drive of Eugene, OR. Portland, OR and Seattle, WA, that’s the list.

Sacramento is a seven hour drive away and Eugene is largely surrounded by more rural locales, including the wide expanses of northern California. Recruiting hinges on flights and direct flights in and out of Eugene are restricted to the major American West metro areas.

The positives for the school include some obvious factors. Most realize that Phil Knight, the now retired owner of Nike, is an Oregon booster and Nike is headquartered in a Portland suburb. Oregon’s flashy, constantly changing uniforms they’ve become known for are a result of having Nike as a benefactor and Knight has helped them keep their facilities competitive. Beyond that, a state of four million people that doesn’t have a NFL team is all the more likely to be sold out for college football. It’s a well supported program overall.

With all of those factors you come to the inevitable conclusion that a successful Oregon strategy has to either be capable of maximizing the sorts of players that can be found in the rural Pacific Northwest or else high level, near-national recruiting, particularly in Southern California. Mario Cristobal is more of a recruiter who’s big picture strategy, as a former offensive line coach for Nick Saban’s Alabama, has been to build champions in Eugene from the trenches. Exactly the sort of strategy that I’m skeptical of as a winner anywhere, much less a place like Oregon.

That said, Oregon had a good year in 2019 and it’s interesting to check out how things are going.

The rise of the Ducks

The first true breakthrough teams for Oregon were the Joey Harrington squads of 2000 and 2001, the former of which I personally remember watching beat Texas in the 2000 Holiday Bowl.

Those teams enjoyed a major schematic edge over many opponents due to their coordinators, Jeff Tedford on offense and Nick Aliotti on defense. The former was an early pro-spread guru who ran single back and double tight end sets but emphasized a “spread to run” approach. Aliotti would guide the formation of top notch Oregon defenses built around speed up until 2012 or so before he retired.

It’s hard to find details on rosters from those times, but the 2001 Oregon offensive line went into the bowl game against Colorado having yielded only 11 sacks all season. They had a pair of Southern California tackles in Jim Adams and Corey Chambers and then an interior line of Oregon locals Ryan Schmid, Dan Weaver, and Joey Forster. All three Oregonians were about 6-4, and around 290. The Ducks had a pair of running backs named Maurice Morris (South Carolina) and Onterrio Smith (Northern California) that worked as a platoon and each had just over 1k rushing yards.

The name of the game was spread running, tall but relatively light offensive linemen blocking zone, and speedy skill players.

Tedford left shortly after that breakthrough success to be the head coach at Cal (Aaron Rodgers era) and the Ducks dropped off until Chip Kelly emerged as the offensive coordinator and eventually head coach.

The best Chip Kelly team was probably the 2010 Ducks who dropped 50 points on Stanford and USC en route to a 12-0 season and Pac-12 title. They played the Cam Newton Auburn Tigers in the National Championship where they narrowly lost, 22-19.

That was another team that nearly ruined the “blue chip ratio” metrics. Oregon’s recruiting was picking up as a result of their high-flying offense and constant uniform changes but the 2010 roster and depth chart didn’t yet incorporate some of the 4-star talents that were heading to Eugene. They were still built mostly from lower rated players.

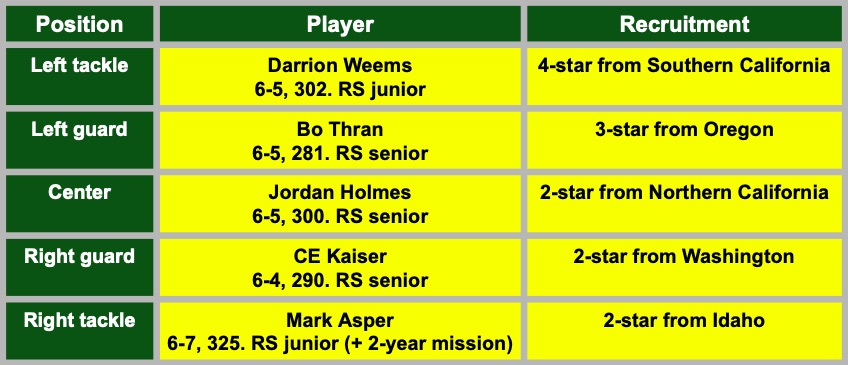

The offensive line was a cohesive, largely senior group with several multi-year starters across the group:

The team was powered mostly by LaMichael James and Jeff Maehl. Lots of people can still probably remember James, a 5-9, 185 pound speedster who ran for 1731 yards in 2010. Maehl was a redshirt senior that was recruited as a cornerback and moved to wide receiver where he honed his craft for years before catching 77 balls for 1076 yards and 12 touchdowns in 2010. They were both 3-star recruits, Maehl from rural Northern California and James a classic #bEASTexas product.

The quarterback was redshirt sophomore and first year starter Darron Thomas, a 4-star from Houston. He was a sturdy runner and a decent decision-maker although he was super jittery early in the championship game. The real oomph of the team was all the ways they could use tempo, motion, and option schemes to open holes for James to burst through.

Things changed with the second Oregon team to appear in the National Championship game, the 2014 unit.

As you can tell, by this point the Ducks had a name that was resonant around LA , allowing them to recruit one of college football’s traditional talent hotbeds. They were also beginning to recruit Polynesians. Grasu and Stevens were both Poly, as well as their superstar, Hawaiian quarterback Marcus Mariota.

The skill talent was still driven by starting multiple running backs, this time though they had 5-star Thomas Tyner as the main back and 4-star Byron Marshall as the RB/WR hybrid along with multiple Californian wide receivers that got into the mix. Much like past Duck squads, they ran a lot of sweeps and outside zone that emphasized having lanky, quick offensive linemen rather than thick maulers. Grasu was notorious for his quickness and capacity to execute reach blocks.

All of these teams also enjoyed good tight ends that could block on zone but also catch the ball. The 2001 Ducks had future NFL player Justin Peele (Bay area recruit), the 2010 Ducks had David Paulson (Washington 3-star), and the 2014 Ducks had Evan Baylis (4-star from Colorado).

For years Oregon’s successes had been the result then of:

-Cutting edge spread to run schemes

-Tall, quick offensive lines with interiors often built from local or regional recruiting executing zone blocking and supplemented by dual-threat tight ends from the same region.

-Multiple fast running backs acquired through national recruiting. For most of their headline teams they’d play both at the same time in spread-option schemes although under Tedford they’d platoon.

Cristobal’s strategy

The first thing that Cristobal, who built his name as the Alabama offensive line coach, tried to implement at Oregon was to get bigger and thicker along the offensive line. Alabama had relied on zone blocking for their own dominant run under Cristobal but they didn’t have lanky, 285 pounders molded from lanky Northwesterners on their line.

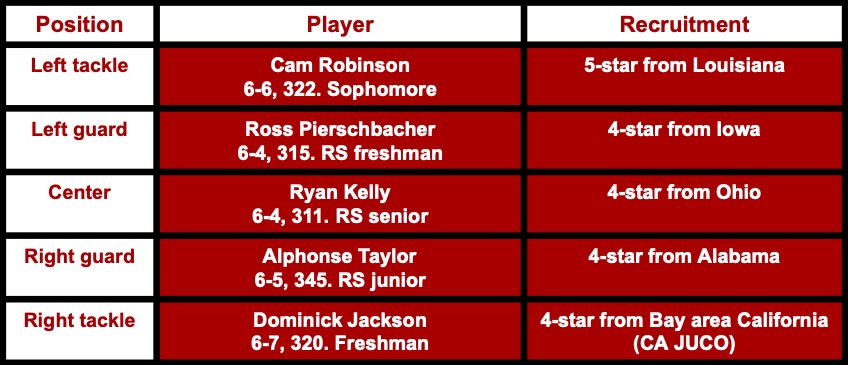

Cristobal’s Bammer lines were often built from players with lower recruiting rankings than you’d think from Alabama’s reputation such as 3-stars Anthony Steen or Austin Shepherd, but they always had some really big, thick dudes. Here was the line they fielded during the one season with Cristobal in which they won a National Championship (2015).

This group was a little higher rated than some of the others in the Cristobal era but it had a consistent composition. They’d play a tall, athletic player at center (Pierschbacher moved inside to replace Kelly who’d replaced Barrett Jones) and they’d often be extra thick and massive on the right side.

Building a similar group up in Eugene would be tough sledding. Those 20 or so extra pounds across the line are a big deal. In the past the Ducks would get guys with long frames and some quickness and bulk them up to numbers approaching 300 pounds, but fielding athletic guys that can execute outside zone blocking at 300+ is another matter entirely.

By 2019 when Cristobal broke through with his first 10-win season and Pac-12 championship, the line’s composition was partway there.

Most of these guys were multi-year starters for Cristobal save for Sewell, who’s one of the headliners of a new era of Oregon recruiting under the new head coach. The Ducks got a little thicker at guard, maintained the traditional Oregon strategy mirrored by Cristobal at Alabama of fielding a tall and athletic center (Hanson was just drafted), and also have a collection of dual-threat tight ends recruited from the region.

Even the dual-running back strategy is still consistent. The 2019 Ducks featured CJ Verdell at running back with Travis Dye doing spot duty as a back-up but they also started scat back Jaylon Redd (5-8, 185) in the slot. The Ducks are now more of a pro-spread team but the emphasis is more on the run game, similar to Texas, than the dropback passing game ala LSU.

For the last two years though, Oregon’s recruiting for the offensive line has looked different than the traditional model. The 2019 and 2020 classes had eight total lineman recruits, three in 2019 and five in 2020, and they don’t follow the “lanky Northwesterner” model of previous eras of Duck dynasties.

Those two classes have included multiple players that will play sooner than later, including some JUCO additions. Here’s the prospective 2020 line for Oregon:

Amongst the players recruited in the last two classes are Aumuvae-laulu (listed at right guard here) and then 4-star Californian Jonah Tauanu’u, 340-pound Utah prospect Logan Sagapolu, 330-pound TJ Bass from a California JUCO, 6-7, 390 pound Fa’aope Sagapolu from Hawaii, and then 2021 4-star Arizonans Bram Walden (6-4, 270) and Jonah Miller (6-8, 285).

Oregon is getting massive and increasingly Polynesian on their offensive line in a hurry under Cristobal.

The future of Duck football

Recruiting thickly built Islanders from within the state and neighboring states is a completely feasible strategy for Oregon, much like relying on lanky, quick kids from rural Northern California or the greater Pacific Northwest was for previous Duck coaches.

Running back has always been a position where Oregon has relied on national recruiting or California, which is still imminently feasible. Tight end is also well stocked but from the normal Oregon recruiting territories of Northern rural California or Oregon itself.

For their final two games and biggest wins in 2019, Oregon went up against two squads with similar program philosophies. The Utah Utes, who they met in the Pac-12 title game, and then the Wisconsin Badgers. Both the Utes and the Badgers are built from the trenches and aim to field the biggest, most physical offensive lines every Saturday. Both schools also maintain a largely regional approach to recruiting, despite pursuing such a difficult task.

The Badgers cull from the German-heavy midwest, particularly their own particularly German farmer-rich state which simply produces an inordinate amount of massive kids that their strength and conditioning program can develop into 6-5, 320 pounders. The Ute strategy is essentially identical to Oregon’s, they take rural Utah kids and Polynesians, each of which are easy enough to find and convince to come to Salt Lake City.

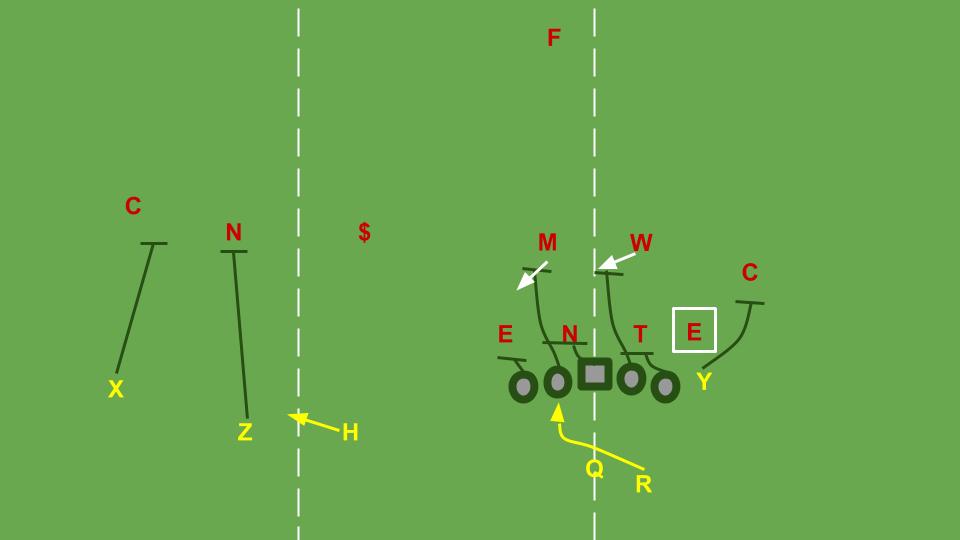

Both of those schools played Oregon with a lot of single-high defense to play their linebackers in the box and force the Ducks to beat them running on talented fronts with the linebackers in the box or else beating match coverage outside.

Beyond playing great defense under the coordination of former Boise State assistant Andy Avalos, the Ducks overcame both Utah and Wisconsin largely by aid of a run scheme known as zone bash.

It’s mid zone or “stretch” zone blocking from the offensive line with the quarterback executing a zone-read on the backside end or outside linebacker. The tight end becomes a lead blocker on a linebacker or safety rather than having to block that end/backer on the edge and the read-player is stressed by the horizontal stretch from the blocking scheme and often unable to defend both the keeper and the cutback lane like he might be able to do on inside zone.

Single-high coverages often don’t do well with quarterback-read schemes, especially if the offense uses motions or nub trips sets like the Ducks often did to get the overhang defensive backs distracted or too far away from the action to help.

It comes down to the ability of the D-line and inside backers to handle the horizontally moving creases created by the offensive line. That’s tough on a play like inside zone if blocked well but when you have really good stretch blocking you even more regularly end up with players up front being asked to play gap control against oversized gaps.

The secondary has little to no chance of getting positively involved, they’re either spread too wide, blocked by the tight end, or 15+ yards deep as the high safety. Against two-high looks the Ducks would involve more RPOs and straightforward runs without involving the quarterback.

In 2020 they’ll have Joe Moorhead coordinating the offense. Moorhead is known for having a cutting edge command of spread-option schemes either in the quarterback run game or with RPOs and they took Boston College transfer quarterback Anthony Brown, who’s been running quarterback-read schemes for the last few years as a starter.

So we’re essentially back to the original Oregon strategy with multiple speed backs and quarterback-reads but with a more diverse composition across the offensive line that reflect changing demographics along the West Coast.

One other feature of Oregon’s time in the sun…

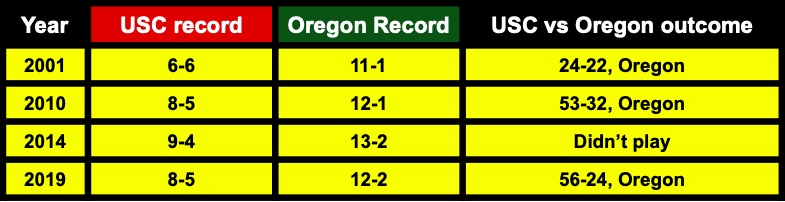

Joe Moorhead and more talented and sizable O-lines are a good way to stay on the cutting edge of spread run systems and build out from the offensive line. However, that’s a tough match for besting USC’s increasingly pro-spread systems that regularly feature highly skilled quarterbacks and receivers, often curated and developed on USC’s behalf (not literally) by local powerhouse Mater Dei high school.

Clay Helton was close to collapsing before hiring Graham Harrell to install the Air Raid but all of a sudden the Trojans have a potent young offense to put on the field and are surging in recruiting. Their 2021 class is currently ranked 4th nationally and includes the next Mater Dei blue chip quarterback (plus another 4-star QB), some Texan skill players, some top-ranked California skill athletes, and of course several tall, athletic offensive linemen.

The other issue for Oregon is the national blue blood programs. They’ve had a couple of high profile games over the last decade with Auburn, LSU, and Ohio State and failed to come up with victories. If your plan is to win via execution and power along the line, then the ultimate proof of concept is to beat a team like Ohio State or Auburn and that just hasn’t happened yet for the Ducks.

I’ve been impressed by how Cristobal has managed to update and maintain the traditional Oregon path to national relevance, in part by adjusting along with the Pacific Northwest’s evolving demographics. But they still have to overcome blue blood talent and pro-spread systems to finally punch through with a National Championship…and that’s another matter. Cristobal had trouble there even while at Alabama.

********

Read about Graham Harrell as a Texas Tech quarterback when the Air Raid and spread passing games were first getting going in my book!