One of the more bizarre and interesting dimensions to the game of football is the way that it recreates the challenges of one of the worst wars in human history. World War I, or the “Great War,” was one of the most cataclysmic events in human history and a precursor to World War II which built upon that foundation of disaster.

WWI was dominated by trench warfare, with millions of men deployed in lines across from each other. Years of advancements in firearms and weapons technology had resulted in modern militaries developing the ability to mass both firepower and man power in ways that would have been unthinkable in previous engagements, save for some foreshadowing in the American Civil War.

The ability to mass enormous armies of ten and hundreds of thousands of men was a product of the creation of the modern state and nationalism. It was a relatively recent phenomenon for the full power of the French state to be harnessed on a battlefield and something that hadn’t been seen consistently in Europe since Rome.

When the ability to muster and field massive armies was combined with the rapidly increasing developments in firepower that were out-pacing evolution in tactics you had the main ingredients for the catastrophe of trench warfare.

Massing hundreds of thousands of men couldn’t make a difference against opposing rifles and artillery and the conflict alternated between periods of men gunning each other down in droves in the open field or else digging down and holing up across from each other. The horror of it all was amazingly well captured in the recent movie “1917” which features a British soldier desperately trying to stop an open field assault. One stirring scene includes the hero trying to ascertain the location of the commanding officer from a captain in the attacking unit, who’s unable to get anything productive out as he sobs uncontrollably while sending his men “over the top.”

Conditions were miserable and casualties were worse. The generals were working out how to solve the dilemmas of trench warfare in live time during the biggest and most encompassing war in history. The consequence of these forces of history all coming to bear was over 10 million dead soldiers, another 21 million injured, and nearly eight million dead civilians. The modern western world died in the mud and trenches in France and was replaced by a more cynical and skeptical post-modern society.

We replay the madness with low stakes in American football. Each team gets an equal number of players that they tend to concentrate at the line of scrimmage. For years the game was even defined by “three yards and a cloud of dust” offensive strategies in which gains and progress were hard to discern from a distance. Hard-nosed coaches egged their players to keep crashing into each other until someone could come out ahead. Tactics centered around either side looking to successfully concentrate numbers at the key spots where they could flank each other.

Despite football’s similarity to the bogged down, fruitless nature of trench warfare, the game has been very slow to move beyond the tactic of simply massing numbers along the lines. Even today, teams and pundits still emphasize the importance of “winning in the trenches” and teams that try to win in other fashions often face a stigma of being “soft” or unable to win a championship.

College football’s most talent-rich and intense conference, the SEC, regularly falls into the trap of trench warfare as they’ve tended to do across the region’s history. The South famously lost the Civil War when a failure by General Robert E. Lee to recognize the reality of modern firepower lead him to open a massed charge by 12,500 men under General Pickett up a hill across open ground into the middle of the Union army (Gettysburg). That lead to 8,892 total casualties, a shift into the war, and ultimately the defeat of the Confederacy.

From then on the Civil War more closely mimicked the coming “Great War” across the Atlantic with either armies digging trenches and hammering each other until the South’s manpower and resources were completely exhausted. Nick Saban’s Alabama dynasty has largely been a reversal of General Ulysses S. Grant’s victory over the South, achieved by massing the full resources and industrialization of the North (endless no. 1 recruiting classes in Tuscaloosa). The defeat of other SEC and national programs at Alabama’s hands have mirrored the fall of the confederacy as they were bogged down in a war of attrition they couldn’t hope to win against the Crimson Tide machine. Atlanta is still invaded every year in a symbolic recreation.

Solving trench warfare

Its always been hard to figure out how to avoid the stalemate of trench warfare, including in the game of American football, in part because the side who was best figuring out the issue in WWI was the losing side. The Germans had two strategic breakthroughs late in the war that nearly brought them victory.

The Germans were doomed by the fact that they faced two fronts for most of the war, facing Russia in the east and France/Great Britain in the West. The British blockade kept them isolated, and then even after Germany (and the red revolution) subdued Russia, the USA then joined the war with France and Great Britain and the exhausted Germans were finally overpowered.

Despite those massive disadvantages, the Germans worked out two solutions to trench warfare, one of which is prominent in a central plot point of the aforementioned “1917.” The movie’s hero is trying to deliver a message to call off a big, “over the top” attack. The attack is occurring because of a successful deception the Germans pulled over on the attacking British unit’s commanding officer Colonel Mackenzie, played by Benedict Cumberbatch. Mackenzie believes they have the Germans on the run and can land a decisive victory that could lead to winning the war.

As it turns out, the Germans are actually employing a new approach called “defense in depth” in which they have multiple lines and yield ground in order to set traps and encourage their opponents to overextend and get trapped. In an era of modern firepower, the defensive position is the best one and being on attack makes you more vulnerable. So the Germans encourage Mackenzie to order an assault into a fixed position and the British send two men to deliver a message to call off the attack when aerial scouts discover that it was a feigned retreat by the Germans.

When the lead character manages to get the message to stop the assault to Col. Mackenzie, Cumberbatch’s character responds…

“I hoped today might be a good day. Hope is a dangerous thing. That’s it for now, then next week, Command will send a different message. Attack at dawn… There is only one way this war ends. Last. Man. Standing.”

Mackenzie just wanted to keep hammering away and be the aggressor in hopes that his side could prove to be the side that is still able to keep their feet at the end. Much like Charlie Strong or Todd Orlando when they tried to blitz their way out of bad situations before getting fired at Texas in 2016 or 2019. Or the approach by the Les Miles LSU Tigers when they’d run power sweep at Alabama over and over again in hopes that they could out-punch the Crimson Tide.

The other solution the Germans worked out was to develop “stormtroopers” to execute “infiltration tactics.” This was in many ways simply the Prussian military doctrine of maneuver, which focused on finding the schwerpunkt or focal point of an opponent’s structure and breaking it down, adapted to the challenges of trench warfare.

The WWI stormtroopers, rather than resembling the clunky and inaccurate buffoons of Star Wars lore, were actually more lightly armed. They were equipped to advance deep across enemy lines, aligned in smaller groups with tons of grenades and light arms.

They’d advance and open up holes in lines or even move beyond the lines to take advanced strongholds beyond the trenches. That’d confuse and open up holes across the lines that the regular infantry could then exploit without getting murdered on obvious frontal assaults against set and prepared lines.

Infiltration tactics were designed to attack and undermine the structure of the defense rather than simply massing firepower and manpower at a single point, like the flank (or off-tackle). The Germans put together a major offensive in the spring of 1918 that achieved major success unheard of in trench warfare only to overextend, become exhausted, and driven back before surrendering.

It took the Germans much of the war to work out how to utilize their preferred maneuver tactics in modern warfare and they didn’t really nail it until the post-war period when it was supplemented with armor and mechanized divisions and became better known as “blitzkrieg.” Other nations picked up on a few aspects of the approach and “maneuver” is the official doctrine of the US Marine corps today.

For years the college football programs that tried to avoid the hammering, last man standing approach favored by Cumberbatch in “1917” were also on the losing side. Texas A&M and Ole Miss had success early on avoiding attrition battles with Alabama only to fold (Ole Miss) or give in and transition to trench warfare.

This was largely because the winning side was the one with greater resources and talent. Alabama mastered the process of fielding super-talented coaching staffs and players so that they could just overwhelm their opponent as General Ulysses S. Grant had ultimately done to the South. For years everyone would hire Saban’s assistants and try to match Alabama’s investment and tactics. Then it flipped, and now the game has changed with “defense in depth” and “infiltration tactics” coming to the forefront of the modern game.

Infiltration vs defense in depth in the LSU title run

Eventually Alabama embraced RPOs designed to help their offense better overpower and flank opponents, which has given opponents fits. It was hard enough to beat the Tide when they aren’t able to isolate 1-on-1 matchups with spread spacing. They were ultimately beaten in 2018 by Clemson choosing to play two-deep and allow the Tide to attempt to hammer the Tigers out of the way in the trenches.

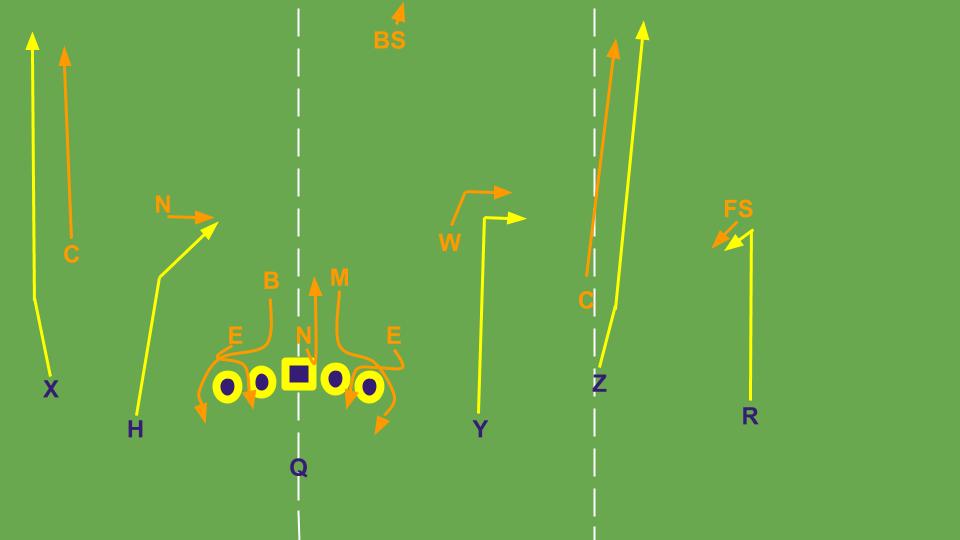

LSU’s 2019 offense was the closest yet to infiltration tactics. Most everything the Tigers did deferred control down to the field level to Joe Burrow and his teammates. They ran RPOs where Burrow controlled defenders with pass options if they tried to mass “in the trenches,” they ran five-man, half-slide protections that had Burrow control blitzers with hot routes, and they ran lots of empty formations that attacked the structure of the defense with spread spacing before letting star receivers run option routes.

Everything LSU did was designed to probe and hunt for weaknesses in the defensive structure so that they could break it down at a fundamental level. They didn’t use the spread to allow them to win in the trenches, they used the spread to find areas where they could undermine a defensive structure, the run game was used only to clean up whatever was left after the opponent was already infiltrated.

No one was really equipped to stop it.

After watching them effortlessly torch Texas’ defense in Austin with this offense, delivering a crushing blow when the Longhorns sent everyone on a 3rd-and-17 blitz only to yield the game-winning touchdown pass, I had LSU pegged for the title. My only real hesitation came when I saw Clemson borrow Iowa State’s inverted Tampa 2 structure in the semifinal against Ohio State.

Playing with a 3-2-6 package and lining up three safeties deep before the snap was, in essence, the application of “defense in depth” on the football field. They encouraged the normally savvy Ryan Day to mimic Col. Mackenzie and order several “frontal assaults” (hand-offs) into the 3-down dime structure only to have defenders materialize out of fixed positions in unexpected places to beat the offense while it was overextended on attack. The Buckeyes weren’t attacking what they thought they were and yielded some run stuffs, tackles for loss, sacks, and interceptions as a result.

I don’t think Clemson and Brent Venables totally understood their own success though and their approach against LSU was designed more to avoid bad matchups and treat the perimeter like the trenches than to repeat the “defense in depth” strategy.

Nick Saban is likely to end his career with a legacy much like the similarly diminutive Napoleon. He’ll forever be remembered for the way that he harnessed the resources of the Alabama program to get considerably more bang for their buck than assumed was possible under 85 scholarship rosters. Ultimately his style can’t hold up as other programs match his resource allocation (or come close) while bringing sharper tactics. Lee’s catastrophic order for “Pickett’s charge” was ultimately a Napoleonic tactic made by a commander that didn’t grasp the futility of a frontal charge. Moving beyond a “win in the trenches” strategy is probably a “bridge too far” for Saban, although they did recruit 5-star, free-styling quarterback Bryce Young.

After years of spread tactical evolution at smaller schools (and in the NFL) LSU picked it up in 2019 and took it to a new level with blue chip athletes. Alabama’s home game against LSU in 2019 was comparable to the “Maginot line” defense of France in WWII. Saban’s stockpiling of big defensive linemen and 240+ pound linebackers intended to give Alabama the edge in the trenches was undone by LSU’s probing tactics and vertical passing. The Tigers simply went around them like the Germans did to the Maginot line with their Tiger tanks.

From here things will continue to develop until college football may no longer closely resemble trench warfare, save perhaps (most ironically) at the service academies where triple-option football is still the name of the game. Some teams will observe LSU and get caught up in the specific plays or tactics, but really it was the infiltration philosophy that made the difference and more teams will catch on to that dimension. Meanwhile, the inverted Tampa 2 structure, or 8-3 defense, will necessarily continue to be developed and applied in new ways as teams build on the concept of “defense in depth.”

With coaching staffs everywhere tied down with quarantine life and little to do save for study film and think, these things may develop more quickly than expected.

********

As usual, look for the Big 12 to be a place where teams get particularly aggressive in pushing forward modern offensive tactics.

Hey Ian. Long time, first time, OU grad/fan here. Just wanted to say thanks for an especially insightful and enjoyable piece. Folks like you, Chris B Brown, Noah Riley and James Light have furthered my understanding of the game immensely in the last few years. And its never more welcome than at a time like this. Fingers crossed for a “normal” season this year. As Lincoln Riley said yesterday, the world is going to need it!

Another thing about “infiltration” tactics was that they acknowledged the futility of managing a grand detailed plan of operations from afar, opting instead for junior officers on the spot to exercise initiative.

(quote from Wikipedia)

The RPO is born!

Oh for sure.

I tried to develop that idea somewhat in the article and definitely in my book. Joe Burrow with authority and options to make decisions pre-snap or post-snap is going to destroy a DC’s gameplan. It’s just more flexible.

Similar dynamic to why Kyler Murray and Vince Young were so freaking hard to stop. The play could start and their speed would allow them to extend things and adjust live in ways that the defenders weren’t equipped to respond to.

No, overall talent is not the problem for Harbaugh’s Michigan – Concerning Sports

[…] The story of the playoff era in college football is that top notch space forces punch above their weight in total recruiting. Overall across the game, what happens on the perimeter is having a greater impact than the trenches. […]