The Briles-era Bears were defined more by anything by Art Briles’ own, unique “Veer and Shoot offense.” There wasn’t another offense quite like it across college football and his disciples still have particular access to some of its secrets even as some of the tactics and style of it have proliferated across the country.

I once noted the difference between the Veer and Shoot and other “smashmouth spread” systems as follows: “Put another way: smashmouth spread teams are various tribes of plains Indians, the Veer and Shoot folk are the Comanche.” Given Briles’ origin out west in former Comanche target Stephenville, TX, this seems especially fitting.

The Bears took every bit of reasoning behind using tempo, power runs and play-action, RPOs, and extreme spread spacing to their logical extremes in the construction of a radical approach to attacking opponents and piling up as many points as possible.

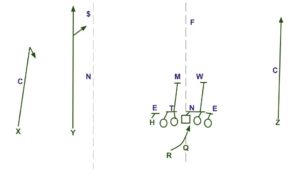

Here was the quintessential Veer and Shoot play:

Here they’re running play-action with max protection but they could also run this play as a straight RPO with a pass/hand-off read:

That’s from the 2012 season, which I believe was the true proof test for the Briles-Bear team. The big question that year was “what happens now that RG3 is gone? Well they put Nick Florence in and he accumulated over 4k passing yards and nearly 5k total yards of offense. On this play they were targeting young Dante Barnett, playing for an injured Ty Zimmerman and still unproven and vulnerable as a young DB.

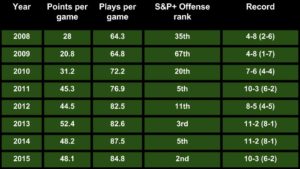

It was all too easy to see 2013 as a likely breakthrough season with a full cast of players chosen and developed by Briles over multiple offseasons stepping in. Sure enough, it was:

The pace and explosiveness of the offense picked up with Bryce Petty at the helm and things didn’t slow down from there, even when Petty was replaced by a combination of fellow RS’d and carefully developed Seth Russell and true freshman Jarrett Stidham. From 2011 through 2015 the Bears were a staple in the top 10 of S&P+ offense.

This identity and culture was THE Baylor brand, what built McLane stadium, and what sent RG3 to New York and the program into the national consciousness. No longer just some small private school that got its head kicked in every year in the Big 12, Baylor was now an offense powerhouse at the forefront of innovative, Texas-based spread offense.

All of that offensive style and culture is gone now, replaced by a coach with a wildly different vision for championship-winning offense.

The Revenant offense

Art Briles liked to score, his plan for winning games at Baylor was to score and to do so at a frequency and with efficiency that you couldn’t possibly match. The true foundation of the offense was the vertical passing game and everything else was geared around allowing the Bears to torch opponents deep. If you couldn’t stop them from throwing it over your head, you had no prayer of keeping up on the scoreboard.

So the Bears would take deep shots and pick on vulnerable DBs early and often throughout games, seeking out ways to get their fastest receivers matched up on the weak links in opposing secondaries. It was truly enjoyable to watch different opponents try to work out how to draw up their defense to survive.

Matt Rhule has a totally different gameplan for handling opposing teams and setting his own team apart in a spread-heavy league like the B12 or AAC. A fantastic example is the 2016 matchup he had with Willie Taggart’s USF Bulls and their “Gulf Coast offense.”

I’ve written a bit about that team, particularly in this article where I explore some of the changes that USF can expect in changing from the Gulf Coast O to the Veer and Shoot now that they’ve hired Charlie Strong and Briles-acolyte Sterlin Gilbert to take over their program.

In short, this “Gulf Coast O” was an RPO system that shared Briles’ appreciation for creating horizontal stress and running the ball downhill, but with QB Quinton Flowers at the helm the Bulls were more about running the ball than taking deep shots and he ran for 1609 yards at 8.7 yards per carry with 18 TDs.

In order to go to the AAC title game out of the East division, Rhule’s Owls had to take down the Bulls. Temple was 2-1 in AAC play going into this game while the Bulls were 3-0 so their victory over USF was crucial for acting as the tiebreaker that put them in the championship game (where they took down Navy).

Rhule’s plan for handling the Bulls included a defensive strategy geared around controlling the USF spread-option attack with dime personnel and Haason Reddick working at the point of attack. On offense, their plan was simple. Ground and pound.

The Owls took the air out of the ball, running it 51 times for 319 yards and controlling the ball for 39:07 of game clock. They frequently lined up in 22 personnel (two running backs, one of whom was FB Nick Sharga, two tight ends) and ran power strong and Iso weak over and over and over again.

The ironic point of this game was that while Temple was successful in controlling the clock, they yielded 6.6 yards per play and 30 points to the Bulls. The reason Rhule’s Owls won the game was that they averaged 7.3 yards per play and scored 46 points of their own.

What Rhule unquestionably took from that game and will doubtlessly carry into Waco is that there’s a marginal advantage to be gained in the modern game from just lining up in big personnel and mauling teams that orient their recruiting choices, development plans, and practice regimens around defending the spread.

While the Baylor offense under Rhule has already been demonstrated to include some spread sets and passing, it’ll also feature a major “four minute offense” component designed to slowly and painfully maul teams at the point of attack.

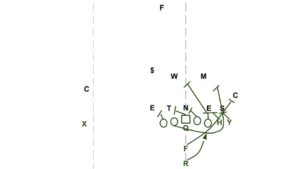

Of course, as we saw against USF it doesn’t necessarily have to be that slow if teams aren’t prepared for it. Here’s an example I’ve mentioned before:

Again as I noted before, rather than looking to get the fastest WR running a deep option route with space in an effort to score in one play, now the goal is to get big bodies on the field and look for opportunities to get a bruising blocker (like Sharga, in this instance) matched up on someone that isn’t going to be up for standing the post. In this instance, they have “power” schemed up where single-digit Sharga is executing a kickout block on a cornerback.

How often do you think Big 12 cornerbacks practice taking on fullback blocks at the point of attack?

Interestingly, smashmouth football was already a significant component to the Baylor offense and Rhule inherited a big OL (albeit a very thin one, depth wise), a pair of big blocking tight ends in Jordan Feuerbacher and Sam Mecklenburg, and also walk-on fullback and former Marine Kyle Boyd.

Building out some various big personnel packages to run “Revenant offense” should be one of the more attainable goals in year one for Rhule and his staff. This package would also make it easy to mix in play-action and get a receiver in a matchup in space without requiring that the Bears have enough receivers to hunt out an opportunity like they would in the spread:

Ultimately the Bears under Rhule will seek to be a multiple team that uses some spread sets and throws the ball around but this will be an easy way for Baylor to maximize what advantages they do have on the leftover roster that Rhule has inherited.

After all, they still have a bevy of solid backs, the bruising blockers I already mentioned, and a strong-armed QB in Zach Smith who’s capable of pushing the ball down the field to isolated WRs on play-action concepts.

The future of Baylor’s offense

The sort of mauling, physical attack that I’ve described above where Rhule’s staff hunts out matchups for big blockers to punish Big 12 anti-spread defenders is going to be a pillar of the #RhuleofLaw, count on it.

Perhaps the more open and intriguing question is what kind of offense they’ll build in the future once they have the kinds of depth and players they’re looking for.

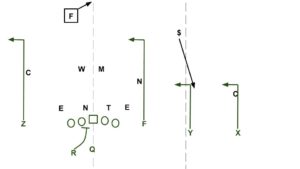

At Temple they made regular use of the same kinds of 11 personnel packages and west coast passing concepts that are currently dominating the NFL. Here’s a pretty typical example of Temple using those components to execute a third and seven against Memphis:

The OL is executing a six-man protection with the RB helping inside and then combining an out route on the boundary with a “levels” concept to the field. The TE is flexed out (F in this diagram) and he’s running a dig with the two receivers outside of him running quick in routes. Levels is a two-deep beater that would allow the QB to make a quick read on the middle linebacker to know whether to throw the dig or the in route to “Y” here.

Temple QB Phillip Walker reads the free safety who tells him what the coverage will be with his post-snap rotation, he’s rolling to the deep middle while the opposite safety is dropping down on the slot to play man coverage. That means that “levels” isn’t going to have a simple read and leverage because the middle LB is going to wall the flex tight end while the strong safety is going to match up on that in-route and possibly get help inside. The in route might be open but it’ll be contested and short of the marker.

However, that rotation means the boundary corner is all by his lonesome handling that out route and Walker nails it with perfect anticipation and placement for a first down.

I’m not sure how effective Zach Smith can be in this kind of concept with time and I haven’t seen much of Anu Solomon here either, but I’d be willing to wager that Charlie Brewer could learn to be very effective in this style of offense.

In the same way that Briles’ offensive system made it really simple and straightforward to get track stars running routes in open grass, the pro-style passing game is all about finding matchups where guys are in the right position to beat coverage with precise routes. Big targets like “flex TE to be” Ish Wainwright or returning wideout Blake Lynch can thrive in this sort of attack where they are looking to get a linebacker or DB on their hip and present a target in a window of time to an accurate QB.

This is a ball-control approach that requires timing and skill and doesn’t necessarily put points on the board in any kind of hurry. On the bright side, when executed at the highest level it is nearly indefensible. This is the kind of offense that Clemson used to beat Alabama. We’ve yet to see Rhule build an offense of anywhere near that caliber yet and the sorts of talents you need to pull it off are big time but the upside of the system is unquestionably high.

The main challenge to that approach is the strain it puts on the offensive line. Mastering both run blocking and pass protection at a high enough level as a unit to ground and pound opponents AND hold up against modern blitz schemes while your QB is chucking it around is intensely difficult. Clemson wasn’t very good at run blocking, they’d use Deshaun Watson’s legs and spread-option ball to run the ball until they faced a really strong defensive front and then they’d turn to their pro-style passing attack as a trump card.

Can you build an offense of that caliber at Baylor? What about a strong enough version to compete for Big 12 championships? That’s hard to say, but this is why landing a cerebral and versatile QB like Charlie Brewer in his first class was so important for Rhule. If they can build a “Revenant” offense that allows them to maul Big 12 defenses with a burgeoning pro-style passing attack featuring flex TEs like Wainwright or Jalen Hurd (the Tennessee transfer) all supported by a typical Rhule defense that definitely make them interesting to say the least.

This is a dramatic departure from the methods that Art Briles used to put Baylor on the map. To go from extreme spacing with track stars to packed in formations with big blockers, freelance spread passing to precise pro-style concepts, and most importantly to go from looking to score every play to carefully controlling the ball and wearing out opponents…that’s about as harsh a culture shock as you could impose on a program.

The Baylor football team will get used to it as they endure Rhule’s practices and are carefully developed to play this style. Baylor fans are probably going to need a season or two to adjust as well, but there is still a revenant of smashmouth, matchup-oriented football here to allow the Bears to continue to haunt the league.

***

Great read. It will be interesting to see.

Do you think you could do an article on smashmouth power running teams, use space and get their best players in space?

Thanks! I might already have something like that, maybe try this bit on auburn:

http://www.sbnation.com/college-football/2017/4/6/15012270/jarrett-stidham-auburn-football-quarterback-baylor

If that doesn’t do the trick ask me a question and I’ll break it down here.

I enjoyed the Auburn article but I still have a question. Its really about space in football in general.

So, the spread offense creates space for the offense by horizontally spreading 3-4 receivers out wide. This decreases the players in the box and in the middle of the field. So my understanding is the space opened up in the middle of the field.

The tighter 1-2 wr formations add players to the box and bring players to the middle of the field thus creating more space on the outside.

If this is correct, and both offenses use of the qb in the run game is the same(whether they run or not), how is there any advantage in spreading multiple receivers to put players “in space” vs getting into tight formations?

Isn’t the space the same but just moved to a different area of the field(from inside to outside)?

The questiin is about about run and pass but, I’m mainly speaking about the run game in particular. Shouldn’t tight formations get their players in space just as easily as a spread formation?

Thanks

Good question.

When you pack in TEs or FBs and bring more of the action inside to the middle of the field you have a few profound impacts on the style of play. One big difference is that it now becomes more about beating blocks in the run game then getting leverage on the ball in space. The RB has more creases to choose from, there are more double teams, and the style is much more mano y mano.

There’s lots of space outside for the receivers, yes, but the windows are hard to hit because they’re so far outside. You need a strong QB to get the ball out there. You watch a team like Texas Tech for instance, their slot receivers are often lined up as far outside as a pro-style team’s outside receivers and they are the focal point of the passing game. The run game when you have big personnel on the field isn’t about space unless you can use your big blockers outside to seal the edge and bounce your RB outside, like Reggie Bush at USC in 2005. If you do that he might find a ton of space to work in but that’s the only scenario where he won’t be surrounded by opponents.

If you start with everyone packed in, there’s a lot of challenges to getting the ball back outside, because the defense doesn’t want the ball to get out there. If you start with everyone spread out, then navigating space necessarily becomes something the defense has to do. Even when they play blocks they have to navigate space to do so.

Any of that helpful?

Yea it helps.

I still am confused about this:

“One big difference is that it now becomes more about beating blocks in the run game then getting leverage on the ball in space.”

I dont understand why this is the case though. If the defense is +1 in the box, what does it matter whether they are are spread or compressed?

If your spread and they have more defenders then you can block you still will have an unblocked defender in your face with no open gaps. Same as with compressed.

And if you have a hat for a hat spread or compressed you now have open gaps and leverage to run. Either eay you need to beat blocks. If Im correct.

I always thought the real reason why spread offenses got players into space and thus created more explosives was personnel.

In compressed 1-2 wide formation you have tight end having to block De’d, and backers. In spread formation generally olineman block lineman, and backers. So now the back has a chance for better blocks to get him more space to attack unblocked defender. And the spread puts more explosive players on the field.

But in the end the space is the same just moved.

The reason I asked was because I found a link to a blog from your site, and found this article: https://breakdownsports.blogspot.com/2015/03/inside-playbook-harbaugh-michigan-power-O-pass-spread-option.html (I don’t think he posts much anymore)

It got me thinking that spread vs compressed sets were neutral as fare as getting playmakers in space. Its just that the spread puts more explosive players on the field (trading TE’s and Fb’s for faster wrs) so there just more explosive threats for a defense to have to deal with.

Thanks for replying. I hope it doesn’t come off as being argumentative Im just a big football theory fan and like understanding the why’s to answers.

“If your spread and they have more defenders then you can block you still will have an unblocked defender in your face with no open gaps. Same as with compressed.”

Only if the extra man is sitting in the tackle box. Otherwise there’s a decent chance that his tackle has to be made in some amount of space. Also there are the quick passes and outside runs that have more space for the bball carrier to use.

“And if you have a hat for a hat spread or compressed you now have open gaps and leverage to run. Either eay you need to beat blocks. If Im correct.”

But remember in the spread that some of the players, like the corners and often 2 out of 3 of the nickel and safeties are playing with more depth and width. They don’t arrive as quickly and with as solid leverage as against a pro-set where they may be within 10 yards or less of the action and closing quickly off the easy reads provided by the TEs.

The advances of quarters coverage are key here because they really frustrate bigger sets. Against the spread those guys are keying slot receivers out on the hash rather than tight ends in the box and they can’t trigger downhill as quickly.

Don’t worry about being argumentative, keep the questions coming!

edit – and how they use space*

Also just read the Clemson vs. Bama last plays breakdown, really great work.

I see what your saying and that makes sense.

This is kind of an related question. So would the air raid production and explosiveness over the west coast offense (which if Im correct where it came from) be do mainly to how much the Air Raid spread its reciever and how many receivers are on the field?

And im talking Texas Tech style air raid vs pass first west coast offenses.

Yeah, Air Raid teams throw more than old west coast teams and they throw it to guys who are in more space, so a missed tackle or bad angle is punished harder.

Sorry to keep bringing this up.

Do you ever think compressed or prostyle sets are preferable to spreads sets depending on your personnel, and not just in short yardage?

I asked because i recently saw a video of Holgerson talk about him putting in the diamond package largely because he had Dez bryant and Jason Blackman on the outside and he wanted to give them more room.

Do you think if you have big time wrs on the outside it would be better to get them space outside by compressing the rest of the offense and leaving them wide? Or spreading is still better in this situation?

I’m pretty sure ok state was mostly spread but i didn’t follow them that much.

Thx

What Holgs was building around was that the most lethal thing they could do was get play-action going to isolate Blackmon on some hapless corner without safety help.

If you are trying to set up a deep receiver from a spread set you need receivers that are dangerous enough underneath to draw in coverage like play-action would. They didn’t necessarily have that but they did have a run game, so they used the diamond and lead runs to suck in safeties.

But now we’re talking about creating space for receivers in the passing game, which is different than creating space for runners.

K-State’s zig maneuver – Concerning Sports

[…] Culture Shock! Part III, the Revenant offense Breaking down Rhule’s smashmouth style and the Temple-USF game. […]

Baylor’s history with the power run game – Concerning Sports

[…] a very effective anti-spread version of the power run game. I called this approach the “revenant offense” since that movie includes a famous scene of Leonardi DiCaprio being brutally mauled by a […]