My main intention with this series was to dive into the differences between varying types of 4-2-5, 3-3-5, and 3-2-6 defensive formations but I hit 1500 words in a hurry explaining how teams will still play true 4-3 and 3-4 structures against the spread so I decided to split this into multiple parts. Today we’ll examine the wide world of 4-2-5 style defensive structures.

The 4-2-5 has been the dominant defensive scheme of the 2010s. It started the decade off with a bang in the 2011 Rose Bowl when TCU beat a power-running Wisconsin team with a pre-B12 recruiting, 4-2-5 roster. Of course by that point Oklahoma had long been using a hybrid linebacker at the sam position, Texas had been using cornerbacks in the nickel since the 2008 season, and LSU was about to send an undersized DB to New York for his play at that spot.

Still, people are generally slow to notice tactical revolutions like this and the game’s narrative centered around TCU as a known “4-2-5” team who was expected to be punished for their diminutive arrogance by big, mighty Wisconsin.

As it happens, the Badgers did hand off to their backs 41 times for 231 yards at 5.6 yards a pop for two touchdowns. The problem is that doing so didn’t allow Wisconsin to light up the scoreboard or control the game adequately enough to overcome their weak passing performance, Andy Dalton’s 219 yards passing at 9.5 yards per toss, or allow them to finish drives better than did the Frogs in a narrow 21-19 defeat.

From there, TCU’s defense took off for a variety of different reasons. One is that it offered much greater flexibility against the spread both in terms of the coverages it allowed a team to play and the way it allowed the secondary to split the field and simplify calls while increasing the complexity for opposing offenses. Another is that it became evident that the six players up front could spill the ball to speed outside against power-running teams well enough that the lack of size didn’t really matter. If you could survive against the run and shut down the pass, as the Frogs did against Wisconsin, then you were in great shape in a modern football game, especially if you could score on offense with your own spread attack.

In fact the way in which the 4-2-5 allowed a defense to bring an unaccounted for extra man against the run from three different positions (thus allowing disguise) was probably a major factor in leading to the popularity of the RPO (run/pass option) as spread teams needed a way to allow their QB to punish teams for bringing that extra hat after the snap.

Finally, the 4-2-5 was much more balanced against motion and other offensive tricks because typically the three safeties would be cross-trained and could bounce in response to motion.

Whether the 4-2-5 will still be a major structure in the 2020’s remains to be seen. I doubt it’ll still look like it did at the turn of the decade under TCU in the 2020s but it may survive with continued tweaks.

The 4-2-5 defense

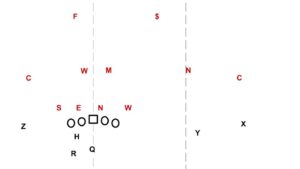

Personnel: Four DL, two LBs, two CBs, three Ss

The 4-2-5 evolved out of both the 4-3 and the 4-4 stack defenses of old. In the same way that the 3-4 defense has added hybrids or nickels (more on that in part III), the 4-3 and 4-4 needed to change up some of the positions and gain more speed to stay relevant in eras where the forward pass was an increasingly major component to offensive strategy.

Overall, the 4-2-5 is designed to do exactly what the 4-3 did but while giving the defense more and better options for handling spread spacing and advanced passing concepts.

Alrighty, let’s talk about some of the main types of 4-2-5, because teams have found a lot of ways to skin this cat.

The Virginia Tech 4-4

The Hokies actually clung to the 4-4 longer than many other teams but eventually converted the OLBs into safeties (the whip became a nickel and the rover a safety) and became more of a quarters team, then a man-free team, then re-integrating their old “nine man front” robber scheme. Their DC Bud Foster is a clever one and he’s been at this for a long time now.

Nowadays they play a wide variety of different zone coverages mixing robber and quarters in a few different ways while trying to ensure that they have guys in position to outnumber the run and to jump routes in the middle of the field.

What tends to set them apart from other 4-2-5 teams is lack of specialization in the secondary. Their corners cloud it up and trap on the edge, their nickel and free safety both carry verticals, and they play a ton of zone everywhere in order to play downhill against run or pass. There aren’t really any coverage specialists or run-stopping specialists anywhere on the field, just well-coached athletes moving around.

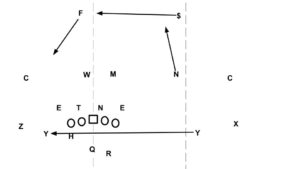

Here’s an example of their propensity to play robber zone coverage that prioritizes positioning guys to attack routes in the middle of the field:

The three safeties (rover, free, and whip) are sitting on the middle of the field routes while the corners play over the top, thus forcing the offense to try and beat their fastest DBs vertically down the sideline. It’s the same principle as cover 2 but with the safeties sitting shallow rather than the corners. They’ll mix in normal cover 2 as well and won’t let you just feast on flat routes all day but this makes for a nasty style to attack on passing downs unless you like your chances at beating their corners down the sideline or navigating their safeties over the middle.

It’s a pretty unique system, although robber coverage isn’t foreign to the other styles we’ll discuss.

The TCU 4-2-5

TCU plays three true safeties on the field but they like to use their “strong safety” (their nickel) as their primary “extra hat” against the run. They also like to keep their LBs in the box when possible so their insistence on those features to their defense have caused problems for them over time in trying to maintain multiplicity against spread offenses that have evolved this decade to hurt them.

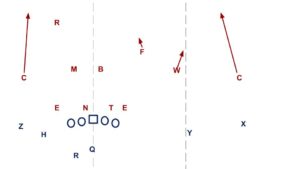

One way in which they became fairly proficient at pulling this off was by mixing in more cover 1, both a pure type that allowed them to load the box with the strong safety…

…and a hybrid type of cover 1 that played like an aggressive brand of cloud quarters by shading the weak safety to the strong side but keeping him on the hash so he could flip his hips and still help the boundary corner.

Nick Orr was brilliant in that role for the last three years, he’s gone now so it’ll be interesting to see what’s next for Gary Patterson. TCU has also become increasingly small and fast across their defense and are veering towards 4-1-6 territory with some of their choices at Sam linebacker with guys like the 5-10, 210 pound Travin Howard. They’re becoming more and more like a 3-3-5 team in that they’ll use speed on the back end AND the DL to move around and outnumber/swarm whatever you want to do on offense. If you’re truly balanced? They can be bowled over like most any other defense as they are built to beat you with numbers rather than in a heads up battle.

The Snyder 4-2-5

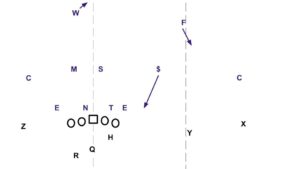

Bill Snyder’s preferred way to run the 4-2-5 is gaining a lot of traction nationally, which is to use more of a C/S hybrid in that nickel spot rather than a LB/S hybrid, in order to free up the defense to play more conservative coverages.

The TCU style of 4-2-5 can still face some of the same issues as the 4-3, with a hybrid S/LB as the nickel LB you are more limited in your coverages. If you insist on using that guy to force the edge as TCU likes to do then you limit what you can do elsewhere and put more stress on your DBs. TCU typically isn’t very good on defense if they don’t have really strong CB play to hold up against that stress and nowadays they ask a lot of their weak safety as well in terms of coverage range in deep zone.

The Snyder 4-2-5 bumps some of that stress back down the DL and LBs and focuses on first shoring up the coverage. In an era where what teams can do to you throwing the ball down the field is the greatest threat on a given Saturday, this style is probably the better practice.

It still features the versatility of the TCU 4-2-5 but actually increases it, and the concern about not having a strong edge defender is less of an issue in an era where teams remove that guy from the run fit with trips formations, RPOs and play-action anyways.

Kansas State has struggled to get an athletic and strong enough defender there since Randall Evans graduated but other teams are employing their base schemes to great effect.

The Wisconsin 2-4-5

This one is really interesting because it comes from a team that bases out of the 3-4 but ends up spending more time in this sub-package to the point where the 2-4-5 is more of their base now.

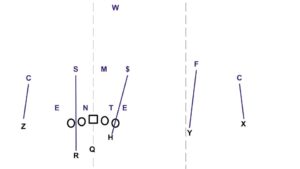

The driving force for Wisconsin and other 2-4-5 teams is that if you have a knack for recruiting and developing impact outside linebackers for a base 3-4 design, you don’t necessarily want to take them off the field. The Badgers tend to crank out excellent inside AND outside linebackers and they aren’t terribly interested in taking any of them off the field, so under Dave Aranda previously and now under Jim Leonhard they’ve been fleshing out a 2-4-5 package that is becoming more varied and deadly every year. Here’s how it looks:

The two inside-backer positions are just like anyone else’s. They read the back and OL flow against the run and in coverage they play shallow underneath zone or match up on a back or TE. The 3-4 OLBs slide inside and play as stand-up DEs.

This is basically one of the ultimate end points for the Over defense in leaning on the DEs to set the edge or spill the ball properly. One of the better or sturdier DEs typically slides inside as the 3-tech and sometimes as the nose as well in on passing downs. Because Wisconsin likes to keep their inside-backers on the field, who aren’t necessarily well equipped to run and cover in space, they play a good deal more single-high coverage than the quarters-based TCU or Kansas State styles of defense.

So if you put four WRs on the field you won’t necessarily succeed in forcing their inside-backers into space because they may just drop a safety down over your fourth wideout. Or they may play one of their many quarters coverages, it’s a very multiple defense they run in Madison.

They don’t just play this straight up as a 4-2-5 all the time either, they make great use of the fact that their OLB/DEs know how to drop and play coverage and their ILBs can always come hard on the A-gap blitz. Their two main ILBs (Ryan Connelly and T.J. Edwards) led the team in tackles and combined for five INTs and five sacks while their three main OLBs (Leon Jacobs, Andrew Van Ginkel, and Garrett Dooley) combined for five more INTs and 16 sacks. Pretty dang good, especially considering that starting the year it was expected that (three-sack) Jack Cichy would be the star and then he was lost to injury. Three-sack Jack (made three consecutive sacks against USC in a bowl game) is off to the NFL now and Dooley and Jacobs are graduating, but obviously they’re going to be pretty good at LB and thus defense again next season.

A theme I regularly find to be true whenever I write about how different teams approach the same problems is that best practices typically aren’t universal. The Wisconsin Badgers tend to find themselves high on versatile linebackers in the middle of the field and less so on elite athletes on the perimeter, so their system is designed to try and get as many backers on the field as possible and to set them up to control the flow of the game.

TCU’s program is built on about snatching up overlooked and undersized athletes from around the state and their system is designed to allow them to swarm the football with those types of players. It wouldn’t really make sense for TCU to be more like Wisconsin or the Badgers to be more like TCU.

A more interesting question is whether their current styles will carry through to the next decade or if they’ll be superseded by other structures, some of which we’ll discuss in part III.

Daily Bullets (February 10) - Big 12 Blog Network

[…] QB Dru Brown….If you like X’s and O’s, these modern defensive explanations have been great (part two-4-2-5 included and three-unique fronts)….Iowa State’s fifth-year quarterback will be back for a […]