It’s very difficult, as you tend to see play out in the Big 12 on a weekly basis. Here’s some notes that the venerable Mike Gundy gave me at B12 media days on the practice:

You know, there’s really two ways in our league. You either gotta defend the quarterback, width and length, or you gotta go get him. If you play traditional, it’s pretty difficult, because the schemes we use in this league are built to find seams and stuff and defenses and quarterbacks are too good. So, you would have to ask these defensive coordinators but, either you better drop back and try to defend him or you better go after him and try to pressure him.

By “drop back and try to defend him” Gundy meant the various drop eight schemes like the inverted Tampa 2 scheme introduced by Iowa State. On the topic of the fire zone blitz, Gundy had this to say:

You know the fire zone was a good scheme for a couple of years and then offenses, uhh, found ways to determine when it was going to happen prior to the snap. So that wasn’t good for defenses. And then defenses started to disguise that a little bit, but because you’re taking and giving up a certain area on the field when you’re fire zoning, if offensive quarterbacks know that they can wear you out. And so, I don’t think that would do much for what goes on in our league.

I also had a brief back and forth with Matt Wells on this topic:

Ian Boyd

Besides your berserker (Wells’ term of endearment) friend Todd Orlando, there’s been a lot of coaches known for being on the cutting edge of blitzing. How do you create a safe pressure blitz in the Big 12?

Matt Wells

Hey, ask TO (Todd Orlando) that question.

Ian Boyd

Have you asked TO that question?

Matt Wells

(Moving on) Umm, that’s a solid question, I respect that. How do you create a safe pressure blitz for the Big 12? Is that what the direct question was?

Ian Boyd

Yeah.

Matt Wells

Man…I think it’s a mix of bringing four, bringing five, bringing six. TO’s gonna bring 7, we’re gonna bring 7 at times, which means there ain’t no free safety back there, my man.

Editors note:

I think you gotta keep offenses off balance, you gotta bring em (blitzes) to the back, away from the back, to the strength of the passing formation, away from the strength, from the boundary, from the field, you can’t be…as soon as an offensive coordinator in this league dials you in? You’re in trouble. Because the talent level at quarterback and receiver in this league is second to none in my opinion. And that’s a major challenge not for Keith Patterson, not for Todd Orlando, but for every D-coordinator in this league every Saturday, which makes it a big challenge to play defense in this league. And I respect that coming in, cause I already know it.

Ian Boyd

It’s all or nothing if you’re going to bring any kind of blitz?

Matt Wells

No, I don’t agree with that. No I don’t think it needs to be all or nothing…

Ian Boyd

I just mean in the package, not on one play…

Matt Wells

If it’s all or nothing someone’s fixing to score. Either it’s going to be the offense’s school song or you’re gonna bounce the quarterback’s head off the turf and you’re gonna pick that football up and run in and it’s going to be the other guys’ (school song). I don’t think there’s going to be many teams go all or nothing with any kind of frequency.

Editor’s note: Things broke down there at the end when I didn’t phrase my question well. I mean that your blitz package needs to have every type of blitz if you wanted to rely on it in your philosophy, because it seemed that Wells was suggesting that bringing only one, or a few, types of blitz means you’re going to get caught and killed.

Defensive coaches are often very aggressive in temperament, and “TO” as Wells affectionately refers to his former assistant Todd Orlando, is certainly an energetic and aggressive figure. The problem in the Big 12 is that “solving your problems with aggression” often just turns into the Somme when your players bravely try to go chase the QB only to watch the ball sail out to someone on the perimeter who then runs free.

Between the way holding is called in the Big 12 and the pace and number of possessions defenses face, there’s a reason that you often see a lot of scoring in the fourth quarter. As hard as it is to pressure a spread offense normally, it’s extra hard when they’ve seen your gameplan blitzes for three quarters and your big men have been chasing them around for 50+ snaps.

One of the big challenges though is simply that spread formations, tempo, and smart QB play tied to smart coordination make it hard for defenses to both disguise where a blitz is coming from and also to cover up all of the outlets the QB has in response.

Here are some of the favored modern solutions for still trying to orient a defense around putting pressure on the offense rather than adopting something more passive, like Gundy’s “just drop everyone and make em earn it” suggestion.

The Wisconsin method

The Badgers have a pretty extensive playbook of blitzes, but a lot of the time they’re bringing four and dropping seven into cover 3:

Either from their base 3-4 or the 2-4-5 that they regularly mix in, the Badgers like to keep four linebackers on the field at all times. That allows them to bring an endless variety of four-man pressures with the two outside linebackers and the two inside linebackers since their front always includes four out of six or seven that know how to play a zone drop.

Here’s how their four starting linebackers are doing this season through six games:

Jack: Noah Burks, 6-2, 241. 2.5 TFL, 1 INT

Will: Jack Sanborn, 6-2, 228. 6 TFL, 3 sacks. 1 INT

Mike: Chris Orr, 6-0, 232. 5 TFL, 5 sacks, 3 PBU.

Sam: Zack Baun, 6-3, 230. 10.5 TFL, 6 sacks, 1 INT

This is a really sensible way of doing things. You’re playing a base defense all the time but you can manufacture pressure by confusing the offense about which four are going to come and from what angles. The driving force of the Wisconsin method is their linebacker corps, they always have four 220+ pound dudes hanging around the box that can quickly involve themselves in the pressure or the zone coverage.

Here are some of the hangups with the Wisconsin method, though. One is that their cover 3 schemes are rarely tested by proficient, spread passing attacks. Texas ran a similar scheme we’ll get to in a moment against LSU, regularly got pressure, and Joe Burrow was able to get the ball out before that pressure landed. If you watch the coverage behind Wisconsin’s pressures you can tell that they regularly benefit from how effective that pressure is at confusing the QB and forcing him off his spots.

The Badgers draw Ohio State in the coming weeks and if they pass that test and reach the playoffs they’ll eventually face Alabama, LSU, Clemson, someone that can really test whether their coverages are going to hold up or not.

Application in the Big 12?

Uncertain. If there was another school that could consistently field four excellent linebackers then perhaps this would work. The state of Texas doesn’t produce linebackers quite like the state of Wisconsin does. Overall I feel confident that Wisconsin’s defense would run into diminishing returns with their style in the Big 12 as teams worked out where the release valves were on the back end.

Zone blitz from dime

That’s how I would describe Todd Orlando’s gameplan for LSU, in which he played a 3-4 scheme like Wisconsin’s base defense but with the 6-2, 210 pound safety B.J. Foster as the “jack” and the 6-0, 205 pound safety Brandon Jones as the “sam.”

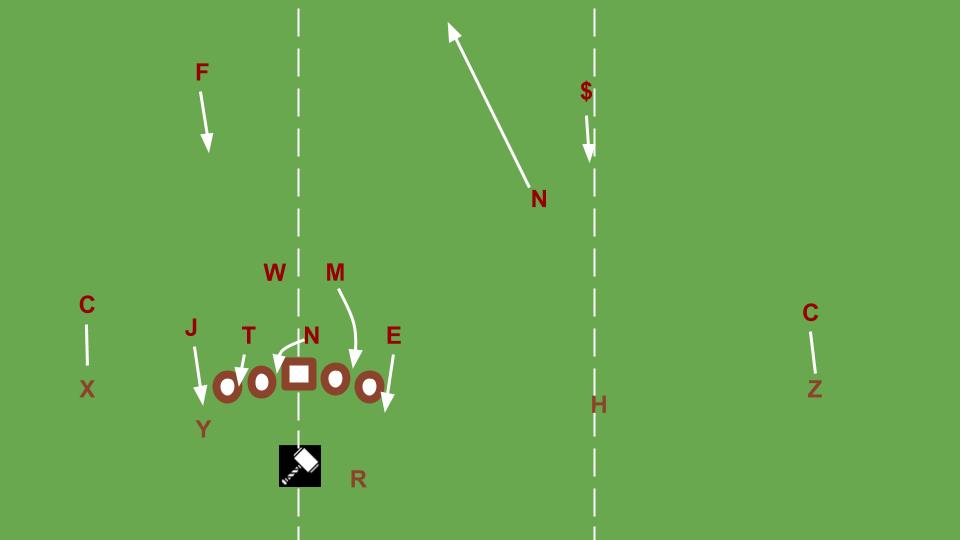

Here’s one of many fire zones from dime that Texas brought against LSU without yielding a positive result:

Texas did sack Burrow four times, but he also threw four touchdown passes and averaged 12.1 ypa while throwing for 471 yards. This blitz notably used BJ Foster (lined up on the line) and Brandon Jones (out at nickel) to get a free run at Burrow for middle linebacker Jeff McCulloch, who couldn’t get there in time. In part because they had the 6-2, 290 pound Malcolm Roach responsible for the drop underneath the receiver, but also because the recognition from Burrow and the timing on that route is nearly impossible to defend if there’s a window to throw the ball into.

Even though Texas’ execution wasn’t elite, the obvious question coming out of this game was whether the zone blitz can even work anymore. Whether playing 3-deep/3-under coverage, even with zone match rules and dime personnel, can adequately defend a high level passing attack.

Again, Texas’ execution hasn’t been exceptional this season but the results are still plenty bad enough to wonder.

There are a few Big 10 defenses executing a lot of zone blitz scheme with much better results than Texas, albeit against Big 10 offenses. The Penn State Nittany Lions, Michigan Wolverines, and the Ohio State Buckeyes, all of which play mostly in nickel.

The Buckeyes don’t bring a ton of blitzes, they don’t have to because they have this guy named Chase Young on their team. The Lions bring more but less so because their linebackers are brilliant finishers in the pass-rush but more because their involvement creates 1-on-1 matchups for their DL, who are all quite good. The Wolverines are the most aggressive and exotic of these teams. None of them have to pass the spread test all that often and Michigan in particular failed it in spectacular fashion on a number of occasions in 2018.

Application in the Big 12?

We’ve seen a lot of teams try this in the Big 12, including teams with talent levels like Michigan, Penn State, and Ohio State can field (Texas and Oklahoma). It hasn’t borne the same kind of results that it does in B1G country. West Virginia has been running a fair amount of fire zone this year, obviously it hasn’t saved them.

Positionless quarters

This would be the Wisconsin method but backed by quarters coverage rather than cover 3. That obviously helps against some of the problems that occur when your defense relies on cover 3 against offenses when they see the blitz coming. Many a Big 12 QB will see single-high and just fire off a fade route to whichever of his receivers have the best matchup, or whichever one is furthest from the deep safety.

Quarters coverage can solve for that problem by getting more safeties in the deep field and putting the free safety on the hash mark. Army runs quite a bit of fire zone AND zone blitzing from quarters, with their own 3-4 defense that has a 2-4-5 nickel sub-package. Texas is ostensibly a positionless quarters defense but they’ve been running more single high this season for whatever reason.

Texas runs the “tite front” on defense, which utilizes three big DL across the front, so we’ve yet to see a team attempt to play positionless quarters behind a 2-4-5 like Wisconsin plays. The idea with “positionless” ball is that you have multiple guys on the field that could end up in multiple positions after the snap. With Wisconsin that flexibility comes from always having four linebackers on the field, the linebackers are versatile and can blitz into any gap or drop into any (or most any) of the underneath zone roles.

For Texas they’ve mimicked that by getting extra safeties on the field rather than outside linebackers, so they have multiple guys on the field that could conceivably blitz the edge, match a slot, play an underneath zone, or even drop into a deep zone. In many ways it’s a more flexible system and more safe on the back end than what Wisconsin runs, but the cost is that you have fewer 220+ pound dudes that can rip through a RB or poorly set OL and go get the QB. Orlando has tended to make up for that by using fire zones that overload the edge with safeties, like the one you can see Burrow beating above.

Texas has, in general, lacked linebackers to feature in the scheme in the Orlando era. Wisconsin regularly has two backers as good as anyone at Texas in timing a blitz and beating pass blocks.

Application in the Big 12?

We haven’t seen the full capability of what this style could do. Texas has tried it from 3-3-5 and 3-2-6 packages with a lot of negative results. Most of their best defensive performances in the last three years under Orlando have come either from playing more inverted Tampa 2 and not being as aggressive (Oklahoma State in 2016 and 2018), or going up against run-centric spread teams that couldn’t protect very well (Iowa State and Georgia in 2018).

A 2-4-5 team that plays quarters and alternates which linebackers are involved in the pressure would be interesting to observe in the Big 12. TCU is the closest you get to that but they are more of a true 4-2-5, even though their DEs often stand-up and occasionally drop into zone coverage.

All or nothing

That’s the term I developed for Tony Gibson’s 3-3-5 at West Virginia, which eventually moved away from that style when they ran out of good transfer cornerbacks. The idea was this, they’d play 3-down with eight defenders off the ball and then alternate between playing drop eight coverage or blitzing as many as six or seven defenders.

You can actually observe a similar dimension to Iowa State this season, who began to mix in more zone blitzes into their package last year and this year regularly dial up big pressures. In a sense they’ve reached something close to what Matt Wells described, where they have an extensive blitz package with multiple concepts. So they are all or nothing both in the sense that Matt Wells meant and also occasionally in the sense that he thought I meant. Because their aggressive blitzes are paired with the ultra-conservative inverted Tampa 2 structure and style, it tends to work out pretty well.

Iowa State isn’t really trying to beat people with pressure, they just have a high capacity for utilizing it as a component to their toolkit.

The 46 nickel

This is how I would describe what Oklahoma is doing this season. The Sooners play some quarters and some cover 3, they aim to win games with their play up front like Wisconsin and they rely in particular on having athletic linebackers around the box all the time. But the Sooners aren’t really doing it with the blitz so much as they are creating the bear front from a variety of angles.

The Ryan bros still use the 46 defense and the bear front, but they tend to mix it in alongside zone blitzes, quarters coverages, multiple DB sub-packages, etc. What Alex Grinch is doing this season is more akin to recreating old Buddy Ryan’s bear front as a way to maintain pressure across the front.

For instance, there’s the third down looks that Oklahoma plays and which I mentioned earlier this week:

That’s a straight bear front that then morphs into a typical four-down pressure after the snap while the jack linebacker drops into coverage (reading the RB). Then there’s the looks that they’re always creating after the snap on first and second down:

Here’s how that confusing mess looks on the chalkboard:

After the snap, Oklahoma creates a 5-1 front with the middle linebacker (Kenneth Murray) blitzing into the place where a 46 defensive tackle would be and the safeties dropping down to match the inside receivers (TE “Y” and slot “H”) and clean up behind while the nickel drops as the single-high deep safety.

If you can beat the pressure up front and get a good ballcarrier to the second level, as Texas did on one notable occasion, then the Sooners are vulnerable. But they typically do a very good job of pressuring up front so that it’s very hard to clear the first level cleanly.

This also plays to the particular strengths of the 2019 Sooner roster. Ronnie Perkins and Jalen Redmond are both smaller DL that could get into trouble if regularly caught with double teams and shoved around over the course of the game, but it’s hard to get double teams against the 5-1/46 defense. Kenneth Murray wasn’t great at diagnosing and filling in Mike Stoops’ two-gap defense, but he’s hell on wheels in this scheme where he’s turned into an attacking piece that regularly stunts and blitzes. OU’s safeties and weak side LBs aren’t even all that great at playing clean up behind this look so the team’s upside in future seasons as those positions improve is a scary thing to contemplate.

So the Sooners aren’t exactly blitzing, really they’re using the 46 defense as a starting point on passing downs and an ending point on standard downs. It’s like a “positionless 46” that moves the pieces around to create the same defense, much like some of the zone blitz schemes mentioned above.

The obvious key to pressuring modern spread offenses is to do so as efficiently as possible and without having to involve the guys on the back end in transparent fashions. Oklahoma’s remake of the 46 defense is an intriguing new way to arrive at that outcome, it’ll be interesting to see how it holds up over the rest of the season as teams start to figure it out and adjust.

********

Learn more about the development of these juggernaut Big 12 offenses in my book:

How different is Grinch’s OU defense from what he was doing at WSU? In terms of approach, not personnel or results.

Similar, I’m not sure how often they built bear fronts at Wazzu. They leaned a lot on Hercules shooting gaps, it might have been pretty 46-intensive, I don’t recall.

Wasn’t the 46 what Virginia Tech used to beat Ohio state in 2014? Looking back, was that a sort of harbinger of what the 46 might do against a spread?

Uh, that was a straight 46 though backed by cover zero. Very aggressive approach oriented around the belief that JT Barrett couldn’t beat their guys in man coverage.

Grinch’s version is more disguised, has more counters, and is more conservative in general.

not much

Who won week 8 in the Big 12? – Concerning Sports

[…] Patterson is in better shape. The TCU defense will be better in another year after a chance to get some linebackers up to speed in the defense and with another year for most of the more impactful DL up front to get better. However, their normal formula has been off of late and the competition is going to be tougher in 2020 than it ever has before. Especially if Ehlinger returns and Texas figures out how to play defense with a roster stocked with NFL athletes. Here’s a hint for Tom Herman, it’s not the zone blitz. […]

K-State and West Virginia, winning with four on defense – Concerning Sports

[…] tell you that they’re a better overall tackling team than K-State or Texas. Meanwhile, Oklahoma has a bunch of talented athletes up front that they love to bring on different twists and s…, so Baylor better have Connor Galvin healthy and everyone well repped on picking this stuff up or […]