Today’s largely accepted wisdom is that you build a National Champion by recruiting the best players in the country, regardless of their location, and assembling your team out of the best of the best. Alabama started to employ that model as the Nick Saban program got going, Ohio State got there as well, and Clemson is now moving in that direction while riding high off multiple title appearances and victories.

From 2007 to 2010, Saban signed classes ranked 12th, 3rd, 3rd, and 4th best in the country. Within those classes, 47.3% of the recruits were from Alabama. From 2011 through 2017 Saban signed seven consecutive no. 1 ranked recruiting classes. These were only 33.5% comprised of players from Alabama.

It’s a normal procedure. Everyone is always trying to recruit the best players that they can and as you win and your national “brand” grows, a larger percentage of the nation’s best players want to come and be a part of your program. Surely that’s the best way right?

I’m not so sure.

Saban’s five national championships are actually clustered in the era when the roster was more Alabama centric, in 2009, 2011, and 2012. Once the no. 1 ranked classes started flowing in, Alabama’s championships started getting more sporadic with a title in 2015, 2017, and none since. In fact, the 2019 Crimson Tide didn’t make the playoffs for the first time in playoff history. Some have blamed their minor drop-off in recruiting, but that drop-off hasn’t dipped them as low as the three early champions.

Ohio State has a similar history, a glance at their 247 pages shows that their recruiting was most Ohio-centric in the lead-up to their 2014 National Championship and has gone more national since. Obviously like Alabama they’ve remained successful, but they haven’t been able to win again. Their 2019 team was lauded by many as one of the most talented squads in college football history right up to the moment when Clemson stopped them in the semi-final.

Clemson has dominated in this period with championships in 2016 and 2018 and playoff appearances before and after. They’re located halfway in between Charlotte, SC and Atlanta, GA. Clemson’s recruiting has also become increasingly national after their successes and after being nearly 50% South Carolinian in the lead-up to the 2016 title is now including much bigger chunks of players from other states. Interestingly enough though, their share of Georgian players has remained pretty consistent at about 25% per class and they’ve also tended to take too many 2/3-star players to rank in the top 5 any year save for the most recent class in 2020.

Is recruiting nationally in order to build the most talented team possible truly the best way to build a champion? Or is it more a luxury of indulgent empire, built on the backs of less heralded players?

The 2000 Oklahoma Sooners

It gets really tricky trying to look back at recruiting in years past. You can’t find rankings on 247 for any year before 2000 and finding recruiting rankings done by 90s figures like Max Emfinger or Tom Lemming is difficult unless you have a box of magazines in your basement.

I’ve always been suspicious of the various proclamations of today’s recruiting gurus. Two years ago I decided to research the Tom Osborne 90s Nebraska teams and found that they were conclusively NOT a team comprised of blue chip players. Blue chip in today’s parlance means “4-star or higher” and the common metric for measuring “championship level recruiting’ is the “blue chip ratio.” The blue chip ratio is the percentage of your roster that is comprised of player that were rated as 4-stars or higher.

The magical number is 50%, you can retrofit that number to every team that has won a championship in the era of service rankings and it will hold true.

There have been some close calls here and there. The 2017 Oklahoma Sooners couldn’t quite clear that bar but they took Georgia to overtime and then could have faced Jalen Hurts with a title on the line in the final. Part of what made the whole metric and exercise extra suspicious to me was that the 2017 Sooners were lead by former 3-star Baker Mayfield and their defense had more talent than their offense yet was considerably less responsible for the team’s relative success.

Here’s the real trick of it. You win championships with elite offense and elite offense doesn’t hinge on elite athleticism so much as team strategy, cohesion, and skill level. Boise State didn’t beat the Sooners in 2007 because they had more talent, they did it because Chris Petersen and Bryan Harsin assembled a clever and effective offense that could execute the “power run game + play-action passing = points” with two-star potato farmers and overlooked Californians and Arizonans running smart play scripts and trick plays.

Elite defense is typically hard to come by without elite athleticism, which tends to correlate with recruiting rankings because elite athleticism pops on film.

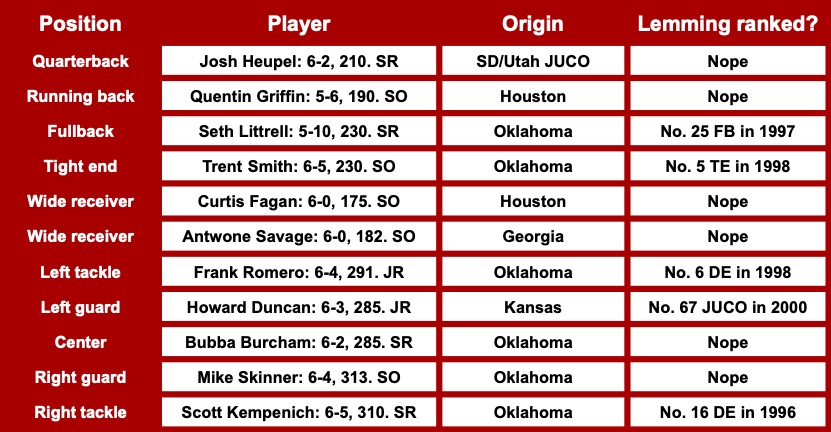

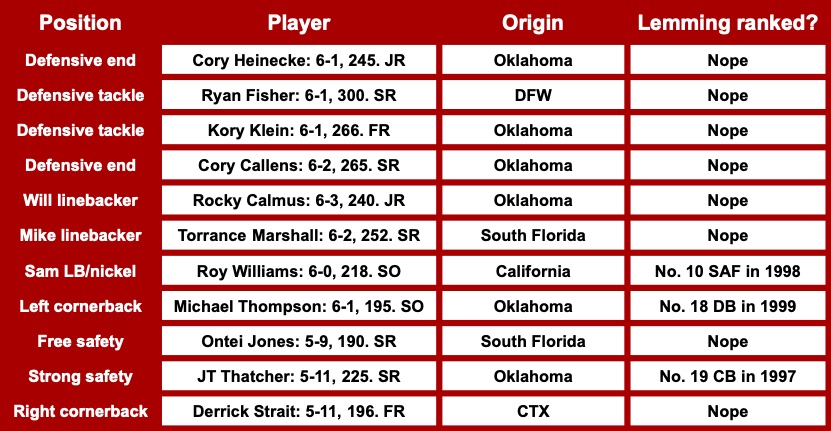

The 2000 Oklahoma Sooners struggled to field either a blue-chip loaded team or an exceptionally athletic one. Here was the lineup they utilized in their National Championship victory over the Florida State Seminoles.

I found a spreadsheet online of Tom Lemming’s rankings of the top 25 high schoolers at each position, which gives some sense of the approximate recruiting ranking for this roster. Another way to arrive at the likely recruiting rank is to check out where the roster came from, and 50% of the starting lineup on both sides of the ball was made up of Oklahomans.

If you’re concerned that I cheated here by omitting key figures from that team, Andre Woolfolk wasn’t ranked by Lemming (from Colorado) and Dan Cody wasn’t ranked and came from Oklahoma. Senior sam linebacker Roger Steffen, who played when OU wasn’t in nickel, was from Oklahoma and unranked. Back-up DE Eric Thunander was the no. 8 ranked LB of 1999.

Suffice to say, the 2000 Oklahoma Sooners weren’t one of the most heralded or highly talented teams of all time. They have guys listed here who were obviously good athletes, but really no more than you’d expect to find on a typical top 10 or even top 20 team. I also tended to look back at them as being an ultra-athletic squad recruited by savvy salesman but poor coach John Blake and then whipped into shape by Bob Stoops and his staff.

Kevin Flaherty disabused me of this notion on Twitter and noted that coaches from that squad regarded it as one of the LEAST talented Oklahoma teams under Stoops, featuring 4.8 athletes in the defensive backfield. Still, their record of achievement that season was remarkable.

We can only speculate what sort of recruiting rankings this team would have derived by a modern system. However if we go back to the earliest date for which we have state rankings done by 247, which is 2002, you can get a sense of how many blue chips the state of Oklahoma might have been producing in the late 90s. From 2002 through 2008 Oklahoma produced 21 players ranked as 4-stars or higher, which is three per year. Oklahoma signed 11 of those 21 in that period. A period in which they where they were one of the hottest brands in college football.

If you do the math for a program with a lot of Oklahomans on the roster that made up half of the starting lineup it’s downright impossible to conclude that they would have met the blue chip ratio. Factor in their low percentage of players amongst Lemming’s top 25 rankings and it’s pretty conclusive.

The 2000 Oklahoma Sooners didn’t win with high level recruiting, they won the National Championship because they “gamed” the system in three key ways.

How the 2000 Oklahoma Sooners won a National Championship

No. 1: They avoided Hurricane season

One useful component to the 2000 Oklahoma Sooners title-run is that while they faced a truly tough schedule, they dodged a couple of juggernauts. Oklahoma’s non-conference was UTEP, Arkansas State, and Rice. The first challenge came from the rival Longhorns, against whom they announced their brilliance with a 63-14 shellacking. The 2000 Longhorns were about a year away due to their reliance on a class of freshman receivers, the 1999 and 2000 Texas teams were basically bridge squads from the initial 1998 run under Mack Brown with Ricky Williams and then the 2001 and beyond teams assembled from Mack’s recruiting classes. Of course later OU teams smoked them too, but we’re specifically talking 2000 here.

The Cornhuskers were good that year and Oklahoma destroyed them with a shocking 31-14 win that I chronicle in my book…

…and they had to beat a good K-State team featuring Jonathan Beasley twice.

But they dodged Miami.

The 2000 Hurricanes were nearly as good as the legendary 2001 Hurricanes, and had many of the same players, but they slipped up against Washington 34-29 in the second game of the season. The new BCS system elevated a Florida State team they’d defeated 24-21 in over the Hurricanes, evidently reasoning that losing to Miami made for a better resume than losing to Washington. In a related story, the BCS method was tinkered with for a few seasons before being scrapped for our new playoff system.

Miami went to the Sugar Bowl, blew out Florida 37-20, and seethed all offseason before unleashing the 2001 beatdown on the rest of college football. Oklahoma dodged that bullet as well thanks to a late season loss to Oklahoma State at Bedlam and a narrow defeat against Nebraska.

The 2000 Oklahoma Sooners had a fantastic resume with multiple wins in a perfect season over top 25 and top 10 ranked teams. But for integrity’s sake it has to be noted that they dodged Miami, that school which handed out the sole defeat to their 1985 National Championship team and then spoiled championships in 1986 and 1987.

No. 2: Position changes!!!

If you look at that table above you see that the Sooners had eight players ranked in Tom Lemming’s top 25 by positions. I’ll list them again here to make plain the dynamic at play:

Seth Littrell: No. 25 fullback, played there for Stoops and offensive coordinator Mark Mangino.

Trent Smith: No. 5 tight end, regularly flexed out in Oklahoma’s Air Raid.

Frank Romero: No. 6 DE, played left tackle for Oklahoma.

Howard Duncan: No. 67 JUCO added for the title season.

Scott Kempenich: No. 16 DE, played right tackle for Oklahoma.

Roy Williams: No. 10 safety, played the hybrid nickel position.

Michael Thompson: No. 18 DB, a starting cornerback.

JT Thatcher: No. 19 CB, moved to strong safety.

Only three of those eight players ended up in the role/position for which they were ranked. The Sooners built the necessary pass-protecting offensive line for their Air Raid system out of converted defensive ends and JUCO additions. On defense they downshifted nearly everyone to field the fastest possible unit.

The Sooners would also slide 265 pound defensive end Cory Callens inside to tackle regularly to make room for freshman Dan Cody or converted linebacker Eric Thunander. Oklahoma also moved Lemming’s no. 19 running back of 1999 Josh Norman to slot receiver and in 2000 recruited Lemming’s no. 8 ranked defensive tackle Jammal Brown, whom you probably recognize as their All-American tackle in later seasons.

This team was faster and more athletic than their rankings would have indicated because the staff moved guys around and played much smaller than everyone else.

No. 3: Cutting edge strategy and tactics

The 2000 Oklahoma Sooners were not only a fast team at many spots but they also embraced more tactics and styles designed to emphasize that speed.

One of my favorite challenges that you hear regularly on message boards or Twitter is this, “when has an Air Raid team ever won a National Championship???”

Let me take you back in time to a moment in time when Big 12 football, and college football in general, was about to change forever.

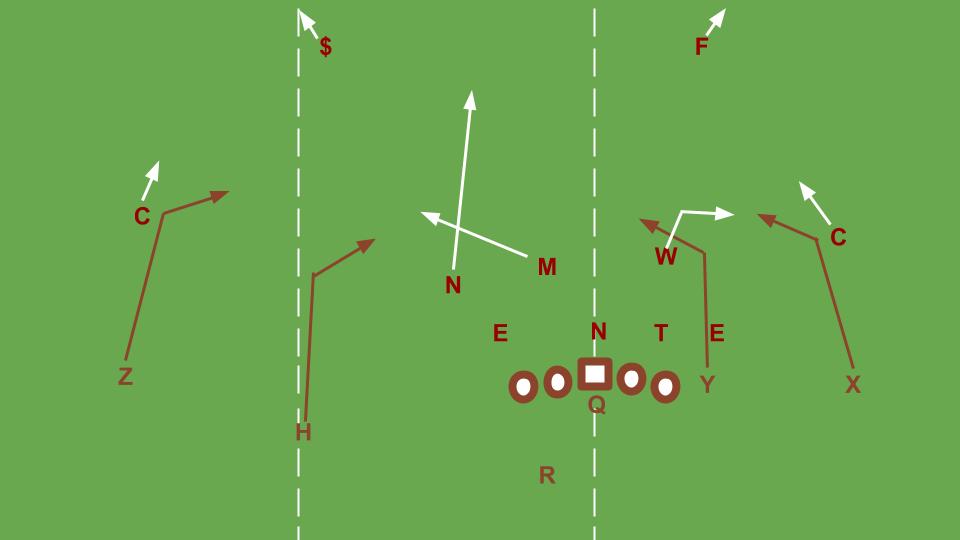

Check out that infographic for the 2000 Longhorn defense, they were crushing teams with the blitz on 3rd down and attempting it here with a fire zone paired with press-man coverage outside.

Check out the Oklahoma offensive line stances and splits, and also obviously the play-call. The OL are in obvious Air Raid stances with fairly wide splits. Out wide they run three routes with vertical stems and Josh Heupel takes the fade to Andre Woolfolk almost immediately at the conclusion of his three-step drop. Touchdown! Boomer Sooner! We’d all hear that song even more than usual that day.

Incidentally, that’s the first Oklahoma football game I ever watched.

This was an Air Raid team, with an early Air Raid playbook installed by Mike Leach and passed on to Mark Mangino, executing an aggressive play-call on a 3rd-and-3 to attack the defensive structure down the field and take advantage of the opportunity to turn Texas’ pressure against them.

The last pre-Stoops Oklahoma team in 1998 had six different players attempt passes for them and it all added up to 183 attempts that yielded 1209 yards at 6.6 ypa with nine touchdown passes and 16 interceptions.

In 2000 Josh Heupel attempted 472 passes that went for 3606 yards at 7.6 ypa with 20 touchdowns to 15 interceptions. His leading receiver by catches was running back Quentin Griffin with 51. Whole new ballgame.

Later in the game down 28-0, Texas inserted 5-star freshman quarterback Chris Simms to try and spark the team. Facing a 3rd-and-7 on his first drive, this happened:

Contrast this with the Texas fire zone above. Oklahoma shows a blitz before bailing their defenders into Tampa 2 coverage and having ultra-quick and extra savvy weak side linebacker Rocky Calmus going where he knows Texas likes to go on this double slants concept and securing a pick-6.

Oklahoma excelled at using nickel personnel to play a lot of schemes that allowed them to confuse opponents into throwing the ball to the wrong place, such as to aggressive underneath defenders playing behind two-deep safeties. The team had 24 freaking interceptions on the year. The two safeties playing over the top in the nickel package, JT Thatcher and Ontei Jones, had eight and five apiece.

They also had a lot of cover 3 match schemes designed to allow them to get Roy Williams flowing down into the box from the middle of the field to stuff runs.

Roy Williams was an absolutely dominant player hanging around the box and the Sooners had schemes to make sure that he was always there, thwarting opponents. A lot of them worked this way, with the linebackers playing downhill in order to channel runs into Williams fitting between the tackles like few safeties have ever done before or since.

As I wrote in the book, the essence of strategy is to play to your strengths while trying to force your opponent to come to grips with their weaknesses. The 2000 Oklahoma Sooners picked their opponents apart by taking football from trench warfare out into space where they’d designed their team to excel.

They didn’t need to be the most talented team because their Air Raid offense and nickel-heavy defense were designed to force more talented teams to beat them in space where they were more skilled, more practiced, and where they had guys like Quentin Griffin and Roy Williams that were as good in that domain as anyone in the country.

Building a National Championship team

Much like many other National Championship teams, the 2000 Oklahoma Sooners won not because they were the most talented but because they were built and deployed to maximize their talent. The 2003, 04, and 08 teams that went to the National Championship games only to lose to LSU, USC, and UF were more talented and included more recruits from out of state, particularly Texas. But they couldn’t win another National Championship.

Is that because national recruiting or trying to build the most talented roster is the wrong approach? Yes and no.

I think teams face diminishing returns at a certain point of talent level because eventually you’re asking 4/5-star players, perhaps from thousands of miles away, to play supporting roles for other players. Many “role players,” particularly on offense but sometimes on defense as well, don’t necessarily need to be ultra talented to get their job done. What they need to be is on point in terms of their positioning and assignment and potentially sacrificial in what they do.

Alabama was able to make the “stockpile as much talent as possible” strategy work to some degree, but the more talent they added the fewer results they got.

What you commonly find with these modern teams is that their initial success before they embraced more national recruiting was often tied to a strategic advantage they had which didn’t require overpowering talent. Urban Meyer’s Gators won with a power-spread approach that denied opponents the ability to stop the run by stretching them out with speed and spacing. Teams couldn’t handle Tim Tebow’s power running when executed from spread sets with Percy Harvin threatening the perimeter.

His 2014 Buckeyes did it with more of a vertical stress, creating a power run/play-action offense from spread sets. Teams couldn’t stop Zeke Elliott with Cardale Jones threatening to take the top off with lobs to Devin Smith.

The early Tide champions did it with overpowering talent but also with lots of pattern-matching defenses and sub-packages that made them a tough matchup. They struggled with the spread and as the spread has become more common amongst teams with comparable talent levels they’ve faded. The Clemson and LSU Tigers pushed the envelop with spread passing, both using four and five-wide sets to attack their opponents and win with throwing. The Tide were lucky that Colt McCoy was knocked out of the game in their first title in 2009 or the weakness would have been laid bare from the very beginning.

Even the Tom Osborne Cornhuskers managed to pull a few higher ranked classes in the later 90s off the marketing of their 94 and 95 titles, but the subsequent teams couldn’t match their precision in the I-option offense.

When opponents catch on to a team’s strategic advantages that powered their rise, there’s not any evidence that national recruiting saved them. What’s more, it potentially damages a team’s cohesion and ability to set up their best players in positions to shine. Florida fell off after Tebow left and their team became infested with criminals that Meyer had recruited. Ohio State’s uber-talented 2019 team had a spread power/play-action dynamic similar to their 2014 squad but Clemson had a more cutting edge defensive response than Alabama or Oregon had in 2014.

For a program to leave their normal recruiting turf to go recruit difference-making talent is clearly a winning strategy. After all, Roy Williams came to Oklahoma from California. Recruiting nationally in order to chase recruiting rankings and blue-chip ratio on the other hand? Questionable strategy. That approach brings no guarantees that your challengers will have to truly wrestle with either your strengths or their weaknesses.

Summary:

#1 I agree with your argument against Bud’s “blue chip ratio” being essential for winning individual national champions.

#2 That said, overall, having elite talent is key to sustained success.

#1

OU 2000 is a good example of more than one of these things.

– Coaching acumen can overcome talent disparity. OU needed to be on the cutting edge on both sides of the ball, as you point out, to overcome the talent deficit. It is rare to have schematic advantages simultaneously so this was a black swan event.

– Depth. OU’s 2000 team had VERY few injuries throughout the year so the Sooners’ limited depth was never really tested.

– The 2010 BCS Championship is the best example of the weakness of the “blue chip ration.” Auburn barely met the ratio (or didn’t, see link below), and Oregon definitely didn’t. https://www.bannersociety.com/pages/blue-chip-ratio-2019

2013 Auburn was just at 50% and also almost won the BCS.

#2

Elite talent is needed to have sustained success. Two things need clarification in this sentence

a. How does elite talent create consistent success (four factors).

b. What is success and how does the Alabama experience in the 2010’s illustrate this?

a. What does elite talent provides

– Culture and expectation of winning.

– Competition for playing time making each individual player strive harder

– Ability to tailor sub-packages with players with high skill level and athleticism

– Depth

b. Success do NOT mean winning national championships, it means competing for them.

Let’s look at Alabama’s best teams as rated by S&P over the decade.

Year S&P Record NC

2010 #1 10-3 no

2011 #1 12-1 yes — made it NC game because Ok St kicker MAY HAVE pushed a kick wide

2012 #1 12-1 yes — in SEC-CG, Georgia was 5 yds from keeping the Tide from the NC game

2013 #2 12-2 no — didn’t make NC game though #2 by significant margin

2014 #1 12-2 no — NC winner was #4

2015 #2 14-1 yes

2016 #1 14-1 no

2017 #1 13-1 yes — needed OT to win over Georgia in the championship game.

2018 #1 14-1 no

2019 #3 11-2 no

So, the Tide finished #1 in S&P seven times. They won the title when they were #1 about half the time (three times). Those three national championships required considerable luck for them to win. This is especially true for 2011 and 2012 where they could have missed the BCS title game both years. Then they also won a title as the #2 S&P team.

The point is that they were in the hunt every year because Saban has built a system that fosters consistent success. Part of this success that is based on having plus athletes who are super focused at every position.

The other part is the Tide running game. Alabama has been so run-focused until they had to pass to keep up. A dominant running game is more sustainable because you can recruit 5 elite OL annually and 2 RB. A bunch of them will pan out. Recruiting QB has much less certainty (although this is changing). Even if you identify an elite QB and develop an elite passing game, QBs can get hurt and don’t stay in college four years.

I think I’m going to reply in another post since this is a fun convo and there’s so much meat here.

A few other thoughts:

– In the first gif, the WR at the bottom would also have been open.

– Simms was a poor tackler.

– OU fans only remember one Roy Williams, at least in the Cotton Bowl.

How could have not been a Sooner fan after that first game?

I lived in Austin when I got into college football, moved there in the late 90s. And I actually rooted for the Sooners some in 2000 because I was awed by that team and enjoyed watching them. Subsequent seasons with Texas as the primary team and regular whippings in the Cotton Bowl quickly turned that initial awe and enjoyment into deep dislike.

By the time it was 2002 and I was in Oklahoma with my Okie grandpa watching Les Miles upset Stoops and spoil the 2002 season 38-28 I was already capable of high levels of schadenfreude. Sooner Grandpa had helped the cause by laughing a few years earlier when we watched A&M beat Texas together in 1999, he got his in 2002 when OSU upset them and then his Okie State grad daughter came over and rubbed it in.

The national recruiting debate continues… – Concerning Sports

[…] commented on my post yesterday about 2000 Oklahoma and National recruiting and there was so much meat to the argument I figured it’d be better to carry on the […]