Around this time last year I was working on my first book. I had decided to scrap the original concept, which was “The 10 greatest quarterbacks in Big 12 history” in order to write what I kept accidentally writing. A chronicle of how the league went from its Big 8/Southwest conference merger and roots in option football to being the high-flying spread league we know today.

In seeking to explain what really made for good quarterback play I kept wanting to explain modern offense and that kept involving telling the history of the league. Once I made that decision, I started writing “Basketball on grass” which intended to use the metaphor of basketball, especially modern spread pick’n’roll basketball, to explain HUNH spread offensive philosophy and developments.

On advice from basketball writer Jonathan Tjarks, I decided to scrap that metaphor and focus on football games and stories that any college football fan would immediately recognize and accept. Then as I found myself repeatedly telling the stories of football programs in more remote locals of the heartland or of Texas, I realized that I was telling the story of “flyover country” driving innovation out of a deep desire to compete and express their culture through football.

At the end of the book I decided to bring things to current events and noted the Iowa State “inverted Tampa 2” defense that they designed in order to give themselves a chance against offenses in this league. In the book…

…I wrote in the concluding chapter:

The Big 12 is now a frontier for pass-first defensive philosophies with the smaller of the two Iowan public universities leading the way, fielding a unit built with Midwestern kids and infused with some 3-star athletes from Texas, Florida, and California. It’s similar to the method that Tom Osborne used to build his lethal I-option offenses at Nebraska applied to the other side of the ball. These principles are already spreading through other Big 12 schools or up from Texas high schools who’ve also been experimenting for ways to handle the HUNH spread offenses.

These counter strategies are almost destined to take hold across the game. With offenses using the passing game to set up the run with RPOs and spread play-action plays, defenses are forced to leave defenders back to stop touchdowns. There’s little point in counting on defenders in the secondary to hold up repeatedly in 1-on-1 situations against passing attacks that are increasingly proficient in order to outnumber the run. It’s the passing attacks that will get a defense beat on the scoreboard. Clemson vs Alabama in the 2018 National Championship demonstrated this and the lesson is likely to be reinforced in future seasons.

Another consequence of this style is the same as what Art Briles found when he began to push the envelope with how he attacked teams down the field in the passing game. When Baylor and subsequent smashmouth spread offenses forced defenses to commit to playing smaller lineups that hung back, they shifted the focal point of the contest back to the trenches where they were at an advantage. If blue blood programs want offenses to have to beat them in the trenches, where the blue blood programs have inherent advantages, then one way to get there is to put so many smaller skill athletes in the back end of the defense the offense is forced to get back to running the ball.

The Texas Longhorns have started to adapt this strategy with their superior talent base and resources, Oklahoma may adopt something similar as well. If you want to glimpse into the future of football, you have to glimpse into what’s happening on the frontier out in flyover country up the heartland of the country and in the rural and suburban locales across Texas that feed their college programs with talent. When you’re playing flyover football on the frontier of modern strategies there’s no choice but to adapt or die.

I had to think about whether I wanted to take a book that was otherwise a nice collection of established trends and stories from the game and end it with a prediction about what’s next. But I decided to go for it, the reasoning seemed pretty solid. If your biggest concern is stopping teams from over stressing your deep coverage, eventually you’re going to have to start weighting your defense from the back end first.

Earlier today I was researching for an article on Texas’ upcoming 2020 schedule and noticed that the UTEP Miners are amongst the teams running a 3-safety, 8-3, inverted Tampa 2 structure of defense.

I broke down the idea behind the inverted Tampa 2 coverage and defense of Iowa State in this post:

In the playoffs I detailed when Clemson was using that structure to stop the Ohio State run game.

A key detail here was that the Tigers didn’t actually play the inverted Tampa 2 coverage, but they got a lot of the same benefits from the structure and pre-snap alignment. The principle that they were really taking advantage of was the “defense in depth” concept that emerged in WWI as a solution to trench warfare:

My only difficulty here in the taxonomy of scheme was that the greater “defense in depth” concept and possible applications of the 3-safety system were beginning to move beyond just the simple inverted Tampa 2 coverage.

Flyover defense

Seth Galina of ProFootballFocus wrote about “3-safety defense” and the responses were absolutely hilarious. Some of the more amusing criticisms he drew included:

-This isn’t a groundbreaking defensive scheme, we’ve had that in our playbooks since the 90s! Here, look at our 3rd down packages!

-3-safety defense isn’t new, genius! It’s called “big nickel.”

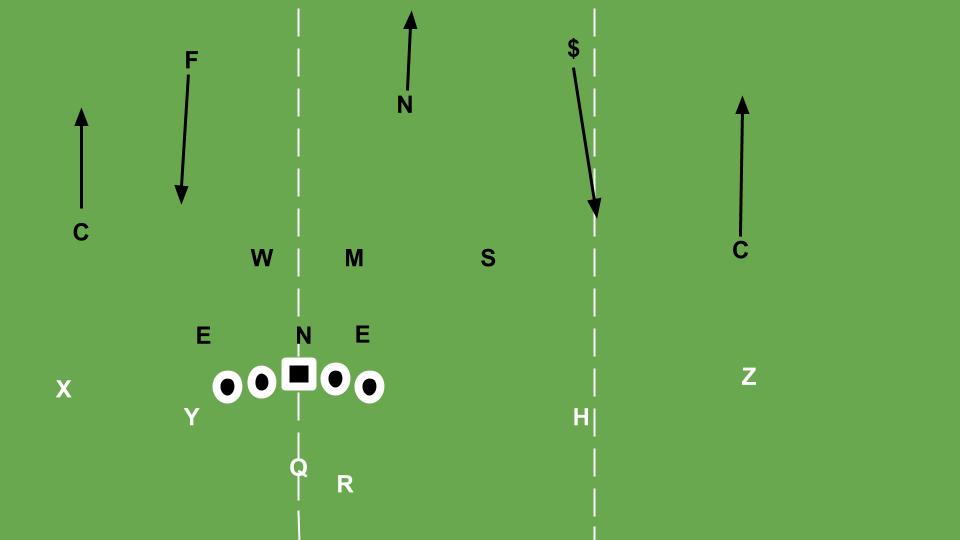

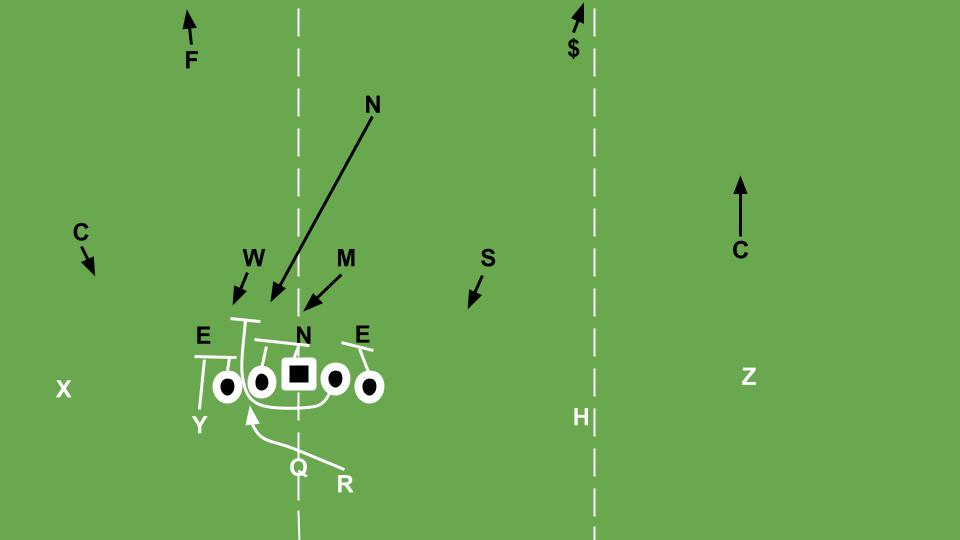

His counters were obvious. It’s not normal to play with three deep safeties before the snap in a sort of dime package as your 1st and 10 defense and he didn’t mean having three players on the field that have an S next to their name on the roster but having three safeties lined up deep before the snap.

Referring to this style as the “inverted Tampa 2” is starting to run into some obstacles. One of them is that there’s another coverage that goes by that name in the NFL in which the corners play the deep halves and it’s not terribly effective. Another is that “inverted Tampa 2” doesn’t seem to be fully conveying the “defense in depth” and pass-first nature of these new designs.

Cody Alexander suggested “Flyover defense” and of course I love it. It’s a nod to my book of course, but also to the origins, and it conveys both the idea of the designs origins as well as the fact that a common effect of the scheme is getting deep safeties buzzing down where the offense isn’t expecting them to be. Such as in this version of cover 3 that Baylor and Clemson both utilized last season:

Or often even better, various quarters schemes that allow the defense to get a safety filling against the run from over the top in unexpected places. In my review of the 2000 Oklahoma defense I described the Sooners’ 4-3 Under defense designed to have their safeties plug aggressively downhill with Roy Williams fitting from over the top:

It’s really easy to get that effect from ostensibly conservative pass defenses in the “Flyover D.”

This is the inverted Tampa 2 coverage. That nickel becomes something like a Roy Williams safety or a Tampa 2 middle linebacker, racing down to clean up runs and often coming unaccounted for by the blocking scheme.

Iowa State used Greg Eisworth there very effectively in 2018 and when their boundary corner can play on the X receiver without help over the top they can get the free safety hawking down as well. It’s like calling in air support on ground targets for the defense, everything looks clear and then suddenly help is coming from over the top and blowing up your run designs.

I was pretty confident when I wrote the book that this was going to be the future but I’m more confident now as we’re watching it play out. So let’s try the “Flyover defense” as a moniker for the new style.

The media’s preseason All-Big 12 teams – Concerning Sports

[…] more importantly is the fact that EVERY team will be highly incentivized to play flyover defense in 2020. If you can stop the play-action pass and RPOs and rally to the run you’ll blunt most […]