In part II the other day, I broached the same topic I’ve mentioned when I was explaining the theoretical advantage of the “bash bros” against the “Raid bros” in the Big 12. That didn’t work out so great, because it turns out that having easy answers for 3rd and 1 isn’t as valuable as being able to fling the ball around and scoring tons of points. Additionally, the various “bash bro” coaches keep failing to keep up with the offensive coaches.

Another important factor in that failed thesis though was that bash bro squadron numero uno, the Tom Herman Longhorns, graduated their chief bashing piece Andrew Beck and didn’t have a replacement. Beck was named the All-Big 12 1st team fullback in 2018, which was really quite appropriate. Beck was listed on the roster as a tight end and he spent some time attached as a tight end and flexed out as a receiver, but his chief value was blocking on the edge as an H-back.

Florida has a similar scheme as Texas, but their tight end/H-back player Kyle Pitts is on the opposite end of the spectrum as Beck. Rather than being a thickly built blocker (Beck was 6-2, 252 pounds), Pitts is lankier (listed at 6-6, 249 pounds) and better as a skill player than a brute.

That does raise challenges though for the Gators that I mentioned. The issue is the same whether you’re in a true Air Raid with four receivers on the field and little water bugs in the slot or in pro-spread personnel with a tight end who happens to be better at posting up defensive backs than base blocking defensive ends.

What do you do if you want or need to run the ball?

There’s four big reasons that a program on the level of a Texas or Florida wants to have a power run game.

- To take advantage of recruiting advantages in the trenches.

- To set up opportunities with RPOs and play-action

- To avoid asking the quarterback to throw the ball 40-50 times and risking injury over the course of the season.

- To have systemic answers to the problems of 3rd/4th and short or goal-to-go.

As we mentioned in part I, Florida doesn’t really have big advantages in the trenches. Yes they recruit at a high level overall and should reasonably expect to bully a lot of the opponents on their schedule, but not all.

The Gators have Georgia and Florida State on the schedule every year, and both of those schools routinely recruit as many or more big bodies in the trenches. Even over in the SEC East, which is a bit tamer than the SEC West, there are still schools that can put multiple NFL defensive linemen on the field on an annual basis. Say what you will about Georgia, Missouri, South Carolina, and Tennessee but the ability to recruit some big boys up front is not a problem.

Setting up RPOs and play-action is immensely valuable, especially if you have really good and fast receivers on the perimeter you’re looking to involve. You can feature those players in the dropback passing game as well but dividing the attention of the defense is obviously highly effective and it makes life easier on your quarterback and offensive line as well. The dropback game is a nice trump card, something you can hang your hat on when the defense has some schematic answers for you to go out-execute them with, but play-action and RPOs are like a strong jab that keeps lesser opponents away.

The wear and tear issue is another major one, if you’re asking your quarterback to dropback 60 times or so a game he’s going to end up with 10-12 scrambles or sacks every week in addition to a bunch of extra shots he’ll take while trying to hang on in the pocket to get a throw off. Go watch Joe Burrow last year and one of the many things he did that was impressive was absorb a lot of hits and stay effective. Texas sacked him four times and knocked him over several other times but they couldn’t speed him up, rattle him, or hurt his ability to throw the ball.

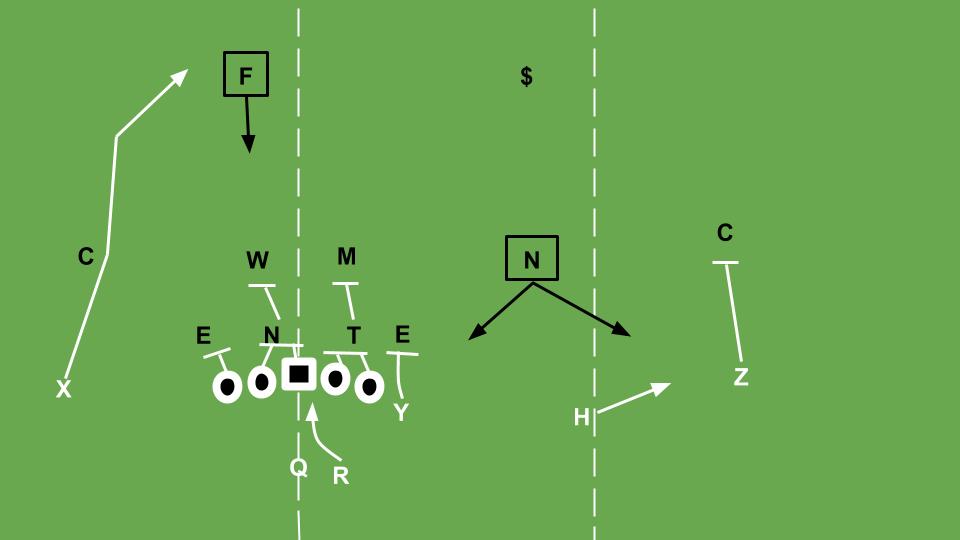

Finally there’s the short-yardage/red zone issue. When the field gets compact inside the 20s, a lot of RPOs stop working as effectively because there’s no space to use in order to create conflict for the defenders. In particular, check out where the safeties line up against a standard Y-off spread formation RPO in between the 20s:

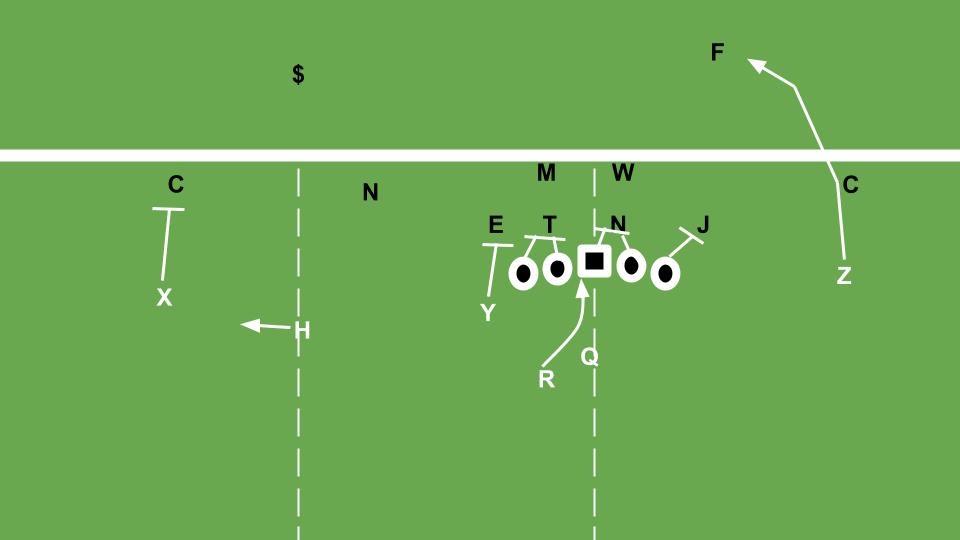

As opposed to how that would look in the red zone:

For the safeties it’s easier to sit on the pass options and still close in time to make a stop against the run. Or, the defense can play press-man everywhere and just park those safeties in the box and let them play run first. The linebackers can plug downhill as well, they’re not reaching a quick pass anyways so they might as well sell out to stop the run.

Red zone RPOs have to involve the quarterback and/or wonky formations in order to create any real space or conflict. If you have a tight end and offensive line that excel at shoving people out of the way as a normal course of operations, that can really help.

Florida may not have either in 2020, so what can they do about it?

What are the solutions for Florida?

Texas-style pro-spread

While Texas also runs a pro-spread offense, they prioritize blocking from their tight end before worrying about fielding a “space force dreadnought” so that their power run game is on stable ground to allow them to mix in lots of runs, work RPOs and play-action effectively, and have a thick quiver of arrows for red zone and short-yardage scenarios. Presumably two years removed from losing Andrew Beck they’ll be able to field another effective bludgeon with senior Cade Brewer (6-3, 250 pounds) or sophomore Jared Wiley (6-6, 260 pounds).

They leave those guys on the field all the time though, Tom Herman has shown a slavish devotion to 11 personnel for the major advantages it brings in the HUNH tempo game. If you don’t substitute, the defense may not be able to either, so if you can get into a power run formation OR a four/five-wide spread set without substituting you can cause major problems.

The Texas method has a ton of upside, but it’s also difficult to properly pull off. Really every system in this vein is difficult to execute because you need a “dual-threat” tight end who can both block on all of your run concepts AND run routes in all of your pass concepts. Beyond the developmental aspect and how long it takes to teach all that to your tight end, he needs to actually be proficient in at least blocking or receiving to really cause matchup problems.

If he’s a lousy blocker then the defense may not be worried about whether or not their dime personnel can stop the run. If he’s a crappy route runner with rock hands how big a deal is it if a linebacker has to cover him in space?

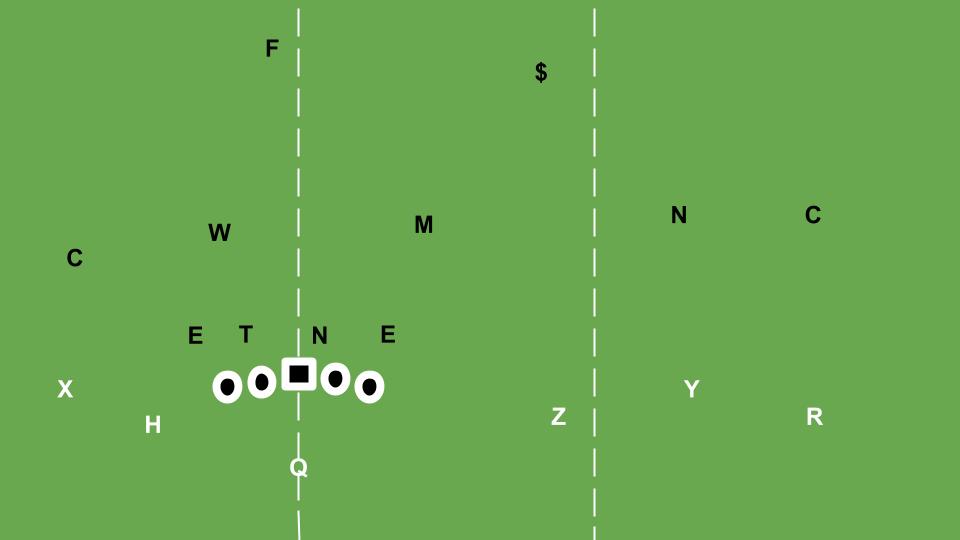

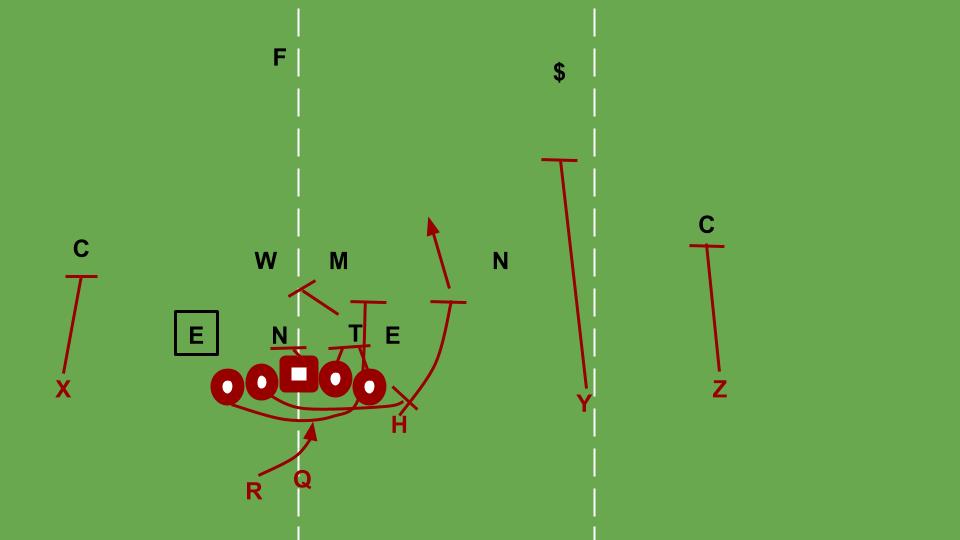

Texas makes sure their guy can block to make the run game work and then they use him primarily as a place-holder in the spread sets. Think the exact opposite of the Y-iso formation that serves to isolate the tight end and more along the lines of:

This is classic pro-spread chicanery. Base defensive structures account for receiving threats from the sideline in so that cornerbacks and nickels stay in space where the ball tends to only travel by air and the linebackers and safeties stay in the box where the ball often travels by ground.

But in this formation, the offense aligns the tight end and running back way out wide while the Z receiver, H slot receiver, and X receiver are all within closer proximity to the quarterback and matched up on bigger, slower defenders. If the defense tries to preserve matchups by sending the linebackers out wide they leave themselves vulnerable to the running back motioning in again to run the ball or, worse, the quarterback running the ball.

With tricks like this, the tight end (and running back) really only need to be fluent in where their routes are supposed to take them on the field to protect spacing and then capable of catching the ball if it does make its way to their hands because the defense has left them wide open.

But none of this applies to Florida, because Pitts is actually one of their best receivers. Not unless they played more 12 personnel and made him into more of a full-time receiver alongside a better blocking tight end.

LSU’s 2019 run game

The Joe Burrow Tigers had some tight ends in Stephen Sullivan and Thaddeus Moss that were really more Kyle Pitts than Andrew Beck. They had (still have) a Beck-lite on the bench named Tory Carter, a 6-1, 250 pound fullback that they lined up in the tight end position when they really needed to run the football. They had some other solutions though that made their run game work and helped Clyde Edwards-Helaire run for 1414 yards at 6.6 ypc with 16 touchdowns.

For starters, they were VERY aggressive with RPOs and the pass game in general. The Tigers didn’t try to move the ball against you, every play they were looking to attack the structure of your defense and score. They were more than happy to chuck the ball if you oriented your defense to stop the run, and they’d keep throwing even if you tried to get into crazy sub-packages like the Auburn 3-1-7.

They’d also throw the ball extensively in short-yardage or the red zone, which is partly how Joe Burrow ended up with 60 passing touchdowns. A lot of team move off RPOs in a situation like 3rd and 1 because the defense will man up the receivers but LSU felt very confident throwing against man coverage. Most of CEH’s rushing yardage came running on packages smaller than nickel or on 5-man boxes that teams yielded trying to deny all the dropback and RPO passes to the perimeter.

But when they had to run the ball on a nickel front, they did have some answers. In particular, their bunch formations.

This is the duo play, which ideally involves two tight ends to secure double teams across the formation. LSU barely had one tight end on the field, but their receivers were pretty big and strong and they repped this play from their bunch formations a lot. What’s more, they generally faced nickel or smaller packages all the time, including on 3rd and short and particularly when they lined up after 2nd down with tempo.

They’re running on a 3-2-6 dime here with Texas using that package to play 3-buzz. The inside-backer play by Texas here foils their ability to stop the run. The Tigers got initial doubles on Texas’ better D-linemen here before coming off when the Longhorns pushed too far upfield.

LSU also mixed in the iso play to avoid asking their tight end to take on particularly difficult blocking assignments, always with pass options outside that Burrow was throwing if remotely open:

Overall the Tigers really knew what they were committing to by using tight ends like Moss and Sullivan that were threats first and foremost as receivers rather than blockers. Their overall philosophy and approach to different downs reflected that reality. CEH also made things work when the tight ends didn’t execute phenomenal blocks by using his lateral agility and the open alleys created by the threat of the pass game to bounce runs outside.

Oklahoma and the quarterback read-game

The tight end’s blocking assignment is made considerably easier when he doesn’t have to block a defensive lineman. If you’re a particularly clever team, like Lincoln Riley’s Oklahoma Sooners, you can regularly involve quarterback run reads without actually having to run your quarterback particularly often.

I detail this in the book…

…Oklahoma’s embrace of the GT counter-trey run scheme and addition of a read element has been an enormous factor in their success.

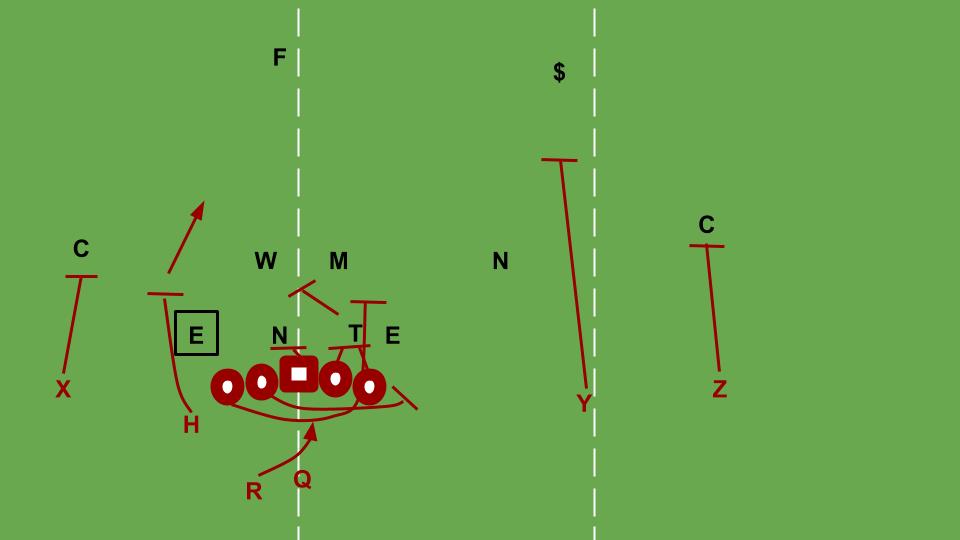

Here’s an example of the kind of thing they’ll mix in:

If that defensive end crashes then the quarterback needs to keep the ball around the edge. However, most teams will try to play this scheme by having the end sit and play contain rather than fully committing to tackling the running back from behind.

The Sooners don’t need the H-back/tight end to block this play against a six-man front. Instead, he can block a defensive back or he can feign a block and then instead run up field and look back for the quick pass.

If the opponent keeps having the end crash after the running back and force a quarterback-keeper, the defense can mix this version in:

Most defenses will play their 3-technique to the same side as the H-back/tight end player. If they didn’t then Oklahoma could use him to block the weak side linebacker for the quarterback keeper and that’s ultimately going to discourage the defense from giving quarterback keep-reads.

Even then, if the defense goes back to having the end sit and play contain, the quarterback can move his eyes and start reading the weakside linebacker to throw the quick POP pass to the H-back if he starts chasing hard after the pulling blockers.

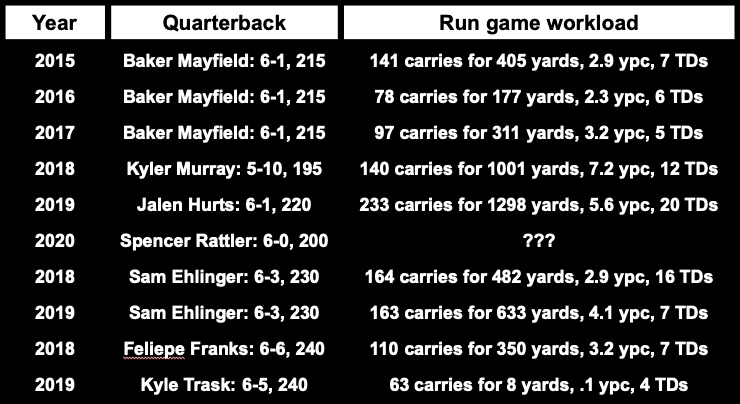

There’s so much Oklahoma can do with this play, all predicated on a willingness to mix the quarterback into the run game now and again. We’re not even talking that big a commitment to running the quarterback either, check out the carries logged by Riley’s Sooner signal-callers compared to Sam Ehlinger at Texas or Dan Mullen’s pair of quarterbacks:

So long as you can configure your offense to be able to make teams really pay if they underplay the quarterback-read option, you can avoid it coming up all that often.

Only one of Oklahoma’s quarterbacks under Riley have matched Ehlinger’s yearly workload in the Tom Herman offense, even though the Herman offense is designed to be less reliant on quarterback run options on the base run (tight zone). Of course, Ehlinger gets extra work because he’s a great short-yardage runner and Texas will mix him in on designed runs and quarterback power schemes. Mr quarterback power himself, Jalen Hurts, is the only one to get a remotely comparable workload and a great deal of Hurts’ carries were scrambles.

Oklahoma often has solid blockers at H-back, but they don’t need them to make their power run game work because they use the option. Florida could mix in more of that and set up Pitts to run routes or pick off linebackers.

Dialing up the Emory Jones package

Last year back-up quarterback Emory Jones had 42 carries for 256 yards at 6.1 ypc with four touchdowns. They’d bring him in periodically for short-yardage plays, red zone plays, or simply as a change of pace. Kinda like Oklahoma’s Belldozer or Texas’ old jumbo formation except that at 6-2, 205 or so Emory Jones isn’t necessarily a power runner like Blake Bell or Cody Johnson.

He’s more like Trevone Boykin or Spencer Sanders, a willing runner between the tackles but more of an explosive slasher than a power back.

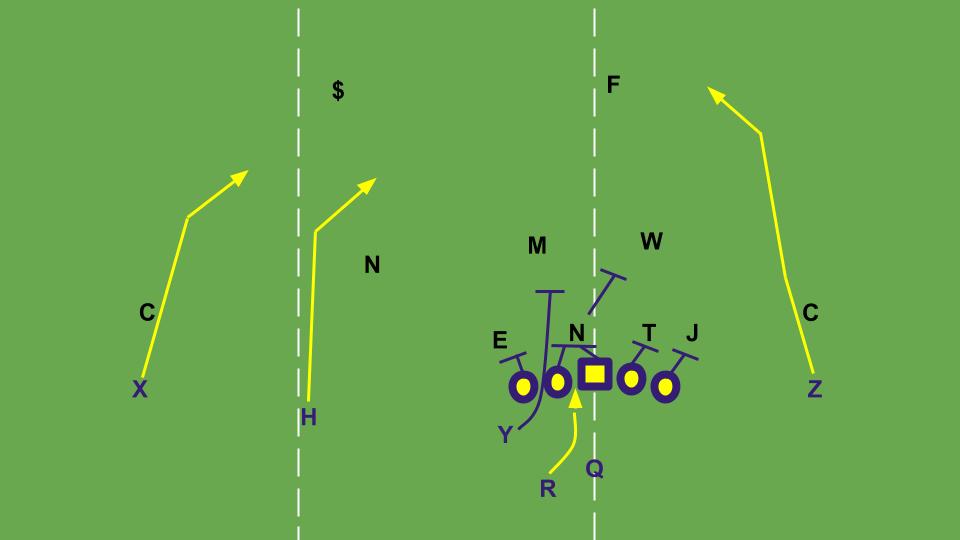

The Gators have a pretty extensive set of plays to use for Jones, including this nice one:

It’s basically counter-trey still but with the H-back as the puller that leads into the hole rather than the tackle with the guard still kicking out on the edge. This is a tougher play to defend when the bubble route runner is basically the running back because it leaves fewer defenders in the box.

Oklahoma (and now Texas, of course) will run the GT counter play at times for the quarterback with the running back running a swing screen to the flat. It’s basically the same concept as this one. The trick with the Emory Jones formation is that the Gators have four receivers on the field and a tight end, much like the Spurrier shotgun spread sets, creating maximal perimeter stress. Jones is competent enough as a passer to really make you pay if you don’t cover those receivers because you’re overly worried about the quarterback run game.

The Gators still need some solutions from above for generating a consistent run game that eats up snaps, picks up chain-moving gains, presents a threat for play-action and RPOs, and occasionally picks up a short-yardage play. However, with sub-packages involving Emory Jones and/or extra tight ends they can manufacture some red zone and key 3rd/4th down pick-ups.

Florida doesn’t need a big time, hang your hat on it power run game. They just need to be able to manufacture one at times to supplement the passing game and convert particular situations. Despite some of the limitations of Kyle Pitts as a blocker and Kyle Trask as a runner, this is probably the easier part. The real key is developing a lethal passing attack with a retooled wide receiver corps during a pandemic. If the Gators get that right, a lot of other things will fall into place and Dan Mullen will have them contending for an SEC title and playoff spot.

What do you make of the sec getting, in effect, an extra month of practice and training as compared to other conferences?

June 8th vs projected July dates

Par for the course, haha. The SEC already takes football more seriously than much of the rest of the country and this will be just another advantage they have as a result of their approach.

It’ll definitely be an interesting dynamic to the season. My home state of Michigan and the nearby, one-time major power that plays before 100+K people 15 minutes from my house is an interesting one to watch. Their president made a comment recently expressing skepticism that anyone around the country would be playing sports in the fall. Is that a genuine belief on his part or is he speaking to the partisan divide in this country over those issues? A lot to sort out.

Run the damned ball, Mullen. | Get The Picture

[…] Ian Boyd reaches the last post of his Florida analysis and asks the musical question, […]

Ian

Great content as usual. Any notion on something similar for Georgia with Monken/Newman?

I’d assume so, didn’t he coach Weeden and Blackmon in 2011 at Oklahoma State?