It’s been interesting to see the Shanahan offense enjoy a resurgence in the NFL game. It’s never really gone away, receiving various tweaks and updates over the years, and the last two NFC champions in the NFL employed modern takes on the original Mike Shanahan offense. First the Sean McVay LA Rams and then the Kyle Shanahan SF 49ers.

These systems are really designed on the same sort of underlying principles as most college offenses. The offense is designed to master a particular style of run blocking, they over stress the defensive front with that blocking system and the threat of constant runs and gains, then they have a passing game built around punishing different defensive reactions.

There’s really three main systems teams are using right now within this broader philosophy, two of which are more common in the college game than Shanahan’s wide zone-based offense.

Inside zone spread

This has been the most common system for a good while now and is currently the dominant style of play within the Big 12. Here are the basic principles.

The offensive line in an inside zone offense is largely interchangeable in that the assignments and rules for that blocking scheme are consistent across all five positions. Obviously the addition of other blocking schemes and particularly pass protection will lead teams to make difference choices at different positions like tackle or guard, but theoretically an inside zone offense is more flexible with who fits where.

A good example of this is the 2017 Auburn Tigers under Herb Hand, who subsequently took over the Texas offensive line. The Tigers trotted out a dozen different lineups that season with the only really consistent feature being All-SEC right guard Braden Smith remaining at right guard. The 2019 Michigan Wolverines were also similar in this respect, all four of their departing offensive linemen heading to the NFL are expected to play guard save for Cesar Ruiz, who will remain at center. They were basically all 6-4 or 6-5 and around 300 pounds.

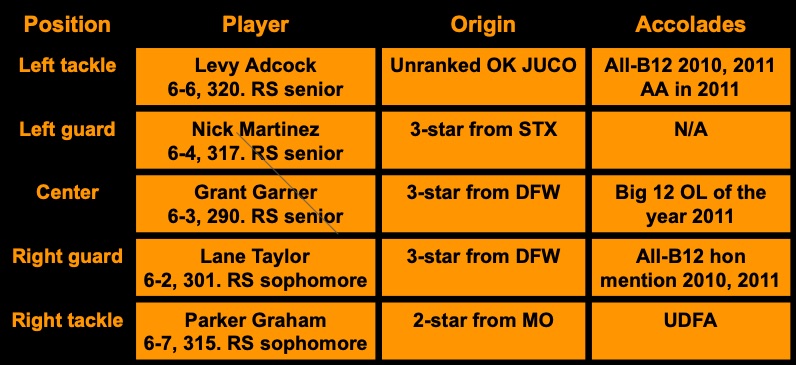

The best example within the Big 12 is the 2011 Oklahoma State Cowboys, who of course won the league championship.

It doesn’t look like much but this group dominated the Big 12 that season. Joseph Randle and Jeremy Smith combined for 299 carries that yielded 1862 yards at 6.2 ypc with 33 rushing touchdowns. Brandon Weeden threw for 4727 yards at 8.4 ypa with 37 TDs to 13 INT and was sacked 12 times for a sack rate of 2%.

Oklahoma State’s run game was built primarily from inside zone with a few variations on the same concept involving screens, fullback leads, fullback traps, etc.

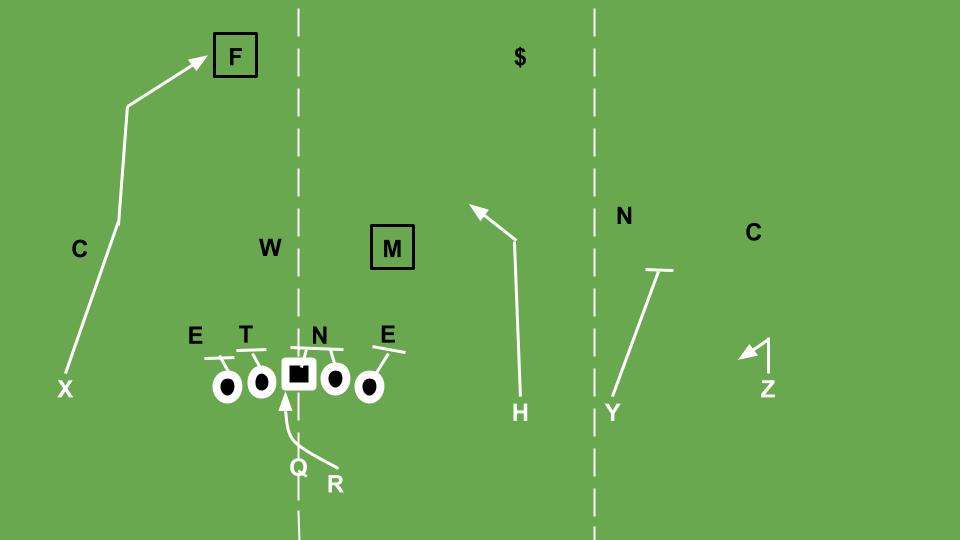

It’s all very simple, the inside zone blocking creates multiple potential creases between the tackles provided that the 1-on-1 blocks by offensive linemen don’t give up penetration and the double team(s) generate push. Defenses have to figure out how to cover all the gaps and stop things before they start in the box, which leads to space and matchups on the perimeter for RPOs, traditional passing, and play-action.

Against a 6-man box from a 3-3-5 or 4-2-5 nickel team, the inside zone spread team just needs a way to account for the 6th defender that the O-line cannot block. They can use the zone-read to “block” one, they can do it with RPOs, or they can put a fullback or tight end on the field to get a sixth blocker. The interior stress of the inside zone pairs very easily with perimeter stress applied by perimeter screens and quick passing and then vertical shots in play-action.

If the offense can consistently win the 5-on-5 battle with their offensive line then they can use the other four skill players in a wide variety of ways to control the potential 6th or 7th defenders in the box. Either by blocking them or with pass options that put them in conflict. In this example there are two potential 6th defenders to control. The middle linebacker, who the quarterback can punish for stepping into the box with the slant by the H receiver, and the free safety he can control with the deeper skinny post option.

The power game

There’s considerable overlap between the inside zone and power run game. Some teams, like Tom Herman’s Texas, Art Briles’ Baylor, or 2019 LSU run inside zone in such a downhill, straightforward fashion that it’s essentially like power. Texas and Baylor also run traditional power schemes as adjuncts to their zone game.

Technically, the power run game is defined by three key features. Down blocking (often by a double team) at the point of attack moving people inside, a kick-out block driving out the edge, and then a lead insert moving in between them to lead the way. Whereas inside zone has some of read and react, hit em where they ain’t or roll with their momentum dimensions, the power game is more about imposition of offensive will.

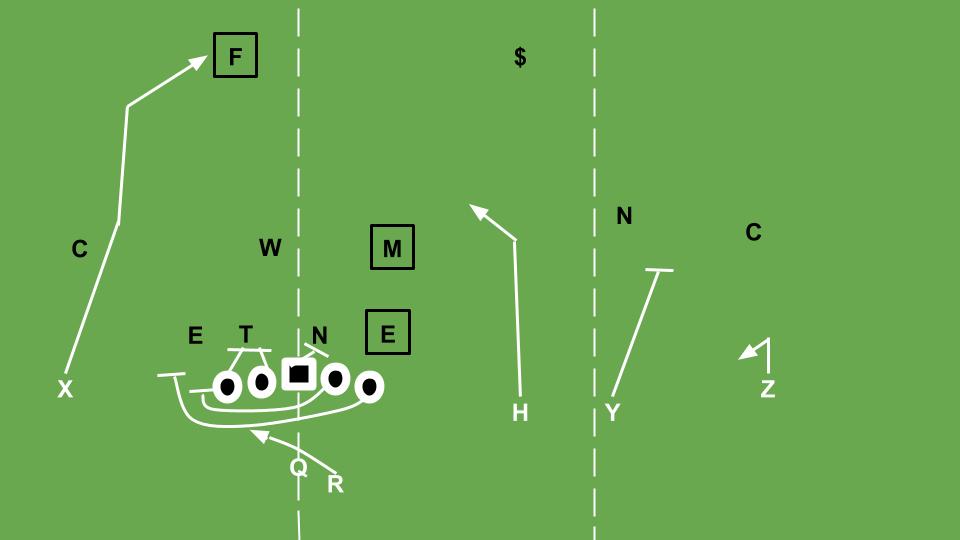

Arguably the best power run scheme in football history is the counter trey, which comes up in my book a number of times:

The GT counter (guard/tackle counter) version has always been one of the best varieties of power. You get a guard executing the difficult kick out block with a favorable angle and then you pull one of the best athletes on your team, the tackle, to lead the way. What’s more, with GT counter you can approach the major plus of inside zone, being able to have a way to win 5-on-5 with your offensive line and creating flexibility with what you do with the other four skill players that aren’t the running back.

There’s a mild hang-up with this version of the play, which is that you need a way to account for the backside defensive end. I detail the evolution of how teams have handled that guy in the book but it’s relatively simple. Teams used to block him with a tight end, Nebraska and K-State later started to block him with the running back so the quarterback could run the ball.

Oklahoma made the play immensely popular under Lincoln Riley by running it like the zone-read with the quarterback having the option to keep the ball and run around the edge if the defensive end chased hard after the running back.

What makes the GT counter play hard to stop with the read attached is that the offense is basically moving gaps over by pulling two linemen. Defenses really get triggered to chase the pullers and crash down from the secondary lest they risk getting totally overpowered at the point of attack. That makes it risky to have your defensive end do more than stay wide in contain to prevent a quarterback keeper. If he blows it against the quarterback, that’s it, everyone else is flowing somewhere else. Texas ran the GT counter-read a fair amount in 2019 and it was relatively uncommon for Sam Ehlinger to pull the ball on the run option because teams normally just left the end home to discourage that option.

Inside zone is a straightforward scheme to recruit and train offensive linemen to execute. You take a lateral step and then just aim to control and whip up on the guy across from you who’s forced to contend with your size in limited space. Power schemes often require having some mobility along the line, particularly if you’re talking GT counter and pulling the guards and tackles.

The best unit for this was the 2018 Oklahoma Sooner line, almost all of which was then immediately drafted.

Some people would call this the best offensive line in Big 12 history, I haven’t really thought about it enough to say one way or the other. One thing is for sure, they were very good at GT counter and they benefitted greatly from playing in front of one of the most athletic quarterbacks in football history and with a lethal play-action game. Opponents were absolutely mauled.

Interestingly, they were more athletic than large, which is partly why the GT counter scheme was so effective with this group. The interior was taller with Powers, Humphrey, and Samia all at 6-4 or better, but Evans and Ford were on the shorter side for your typical tackles. They just had great athleticism and long reach.

Ironically, inside zone is often more about having big, powerful offensive linemen that can whip a guy across from them whereas the power game is often more about quickness and athleticism across the line. You can’t expect to overpower an opponent consistently without angles and movement. Many times inside zone is more of a “cover them up” sort of scheme that focuses on not getting beat and letting the spacing, double team, or running back make things work. Power is more aggressive and thus can pair more effectively RPOs and particularly with play-action. But the line has to be able to win with it.

Shanahan’s wide zone

You don’t find a lot of “wide” outside zone in the college game. It’s there, some teams mix it in and some do indeed use it heavily, but inside zone and other schemes are much more common.

It’s sort of a strange phenomenon worth a closer look considering that some of the best outside zone teams have more approachable personnel for the typical non-blueblood college program than does power or even inside zone.

Here was one of the best outside zone teams at the college level in 2019.

This team, Appalachian State, went 13-1 and won the Sun Belt and then the New Orleans Bowl. Their running back Darrynton Evans ran for nearly 1500 yards and then was drafted in the 3rd round by the Tennessee Titans. Their first year head coach was Eliah Drinkwitz, who was then hired away by the Missouri Tigers. Their offensive line coach Shawn Clark was named the new head coach.

As you can tell from the summary above, their offensive line was pretty small and two of their starters were rated as defensive ends (and were closer to 230) coming out of high school.

Outside zone blocking is all about having quicker linemen that can beat defensive linemen to spots laterally and then generating creases from that initial stress. If they can do that at 6-5, 320 that’s great, but often the 6-2, 285 pound dude can also handle that job just fine and there’s more guys who match that description who can pull it off.

To reference a post from the other day, Nebraska’s elite offensive lines under Tom Osborne and later Frank Solich regularly included lots of 6-3/290 type Nebraskans that excelled in a Nebraska run game that included mostly outside zone and power blocking.

The fascinating question is why this style isn’t more prevalent in the college game. Particularly considering how teams can build truly lethal attacks with lower rated recruits. Finding sturdy, 6-3, 290 pounders that can move isn’t near as hard. It’s finding the bigger dudes that can maul a guy heads up, or the tackles that can hold up in protection on the edge, where things really get difficult.

Oregon used to use more outside zone under Chip Kelly back in the day and found that it was easier with their smaller, “locally sourced” offensive linemen. Additionally, outside zone with a good tight end is even better and easier. Now they’re moving more towards inside zone, particularly with Joe Moorhead and his inside zone spread coming up to Eugene.

Here are the main reasons why you don’t see outside zone as often in the college game.

It doesn’t work particularly well from the shotgun.

True wide zone schemes are designed to have the running back aim for the offensive tackle’s outside hip at the snap and then make a decision from there to maintain that track, to bounce the run wide if the offense hooks the edge, or to cut back against the grain. The wide zone cutback is typically where the real money is made on this play.

The problem in the shotgun comes from asking a running back who starts the play behind the opposite guard of the offensive tackle he’s aiming at, to build up speed to credibly threaten the edge within the normal timing of the play.

The running back has to be awfully quick to make this work, which defeats one of the great benefits of the Shanahan wide zone system. The 49ers are simply the most recent team to reveal that when you get the wide zone system right, the back isn’t terribly important. Any good athlete that you can train to follow his keys can find success on a stretched out, pass-conflicted defense.

Often you’ll find big, powerful running backs excel in wide zone because they get set on a trajectory to the edge that is terrifying to opponents and then can cut back and just run downhill on people. Not so with the shotgun though, those guys typically don’t have the quicks to credibly threaten to bounce runs wide from this starting point.

There’s also the fact that the alignment of the back gives away where the play is going. There are teams that will run wide zone from the shotgun and have the quarterback turn and hand the ball to the running back for him to run to the same side he starts on. That helps avoid obvious tendencies but it still requires tremendous lateral quickness from the running back.

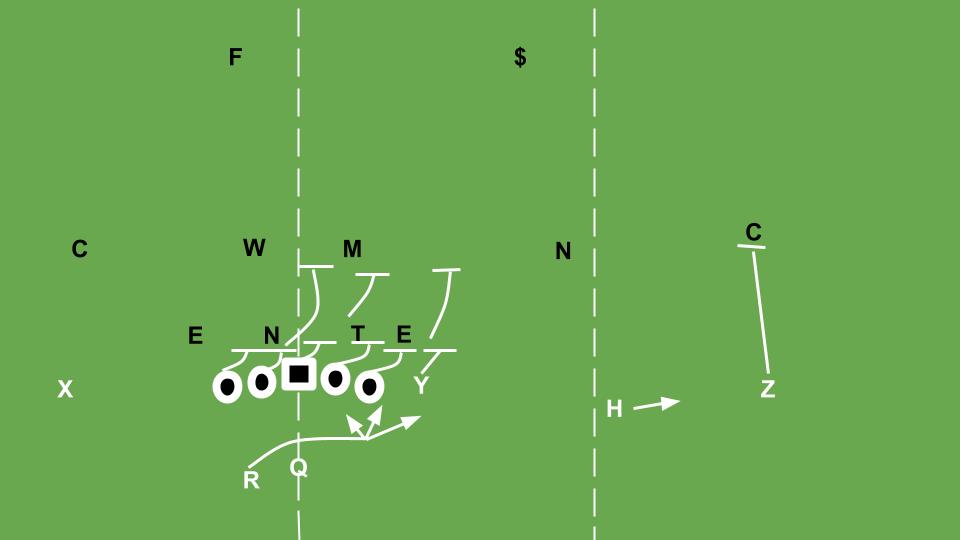

Here’s how Appalachian State liked to run wide zone last season:

They’re in the pistol for starters, which better mimics the angle and trajectory for the play you get from under center. That’s partly why this play works better in the NFL, because of the under center angles and the tighter hash marks that create more spacing to either side. The Mountaineers also have a receiver motion away from the play to increase the lateral stress and create false keys for the defense.

When you see a spread college team line up in the pistol every now and again, you better expect them to run wide zone.

It doesn’t work particularly well with RPOs.

The pistol formation in particular doesn’t work well with RPOs. The quarterback has to turn to hand off the ball and create the favorable angle towards the perimeter, which means he can’t pull the ball out suddenly to throw a slant. If you have a back that’s quick enough to execute the play effectively from the shotgun but you attach RPOs for the quarterback to read while putting the ball in his belly, you then slow him back down and risk foiling the timing of the play again.

NFL teams that mix in a ton of run/pass conflicts with wide zone typically do it with rollouts, bootleg, etc. Any reads to pull the ball out and throw it tend to wreck the design.

You can run zone-read with wide zone blocking, in fact it’s often extra effective because it creates even more space on the backside for the unblocked defensive end to try and manage. You can run option with it from the gun or under center, that’s essentially what Nebraska was doing.

You can also give your quarterback pre-snap RPOs to throw if he sees the right leverage and mix in traditional play-action, but the goodie bag of modern RPOs is much more difficult to incorporate. That’s a steep price.

Boundary and field hash marks

I touched on this above but it’s a pretty big problem. Oklahoma used to run wide zone a lot more earlier in the decade and they could get fairly transparent with their running game. Typically you want to run it to the field because there’s so much more space than to the boundary, but that’s going to create some major tendencies. If you run it into the boundary then you can mix things up more but you also have to sacrifice some space.

It’s less of an issue from under center because the timing of the play is easier to manage, but if you try to regularly run it from other looks that complicate the timing then it’s just one more confounding factor.

Quarters coverage

College defenses largely use quarters these days. Which means that those safeties can trigger downhill on run reads if they don’t get signals from the slot receivers or outside receivers that tell them to stay deep.

Outside zone is pretty obvious because of the wide lateral steps by the offensive line and since RPOs are harder to execute teams will often have the tight end or even a fullback or a second tight end all helping to block. That solves the problem of blocking outside linebackers that you can’t control with RPOs, but it also invites those safeties to come downhill and make a mess.

NFL defenses prefer to play in single high, which is less effective at sending either safety to help stuff the run game. You crease a single high defense with wide zone and you can do real damage, but a quarters team could have a safety waiting to clean up the mess to either side of the formation.

So one of the all time great run blocking schemes which has made champions of underdog, undersized lines at every level of the game has often been sidelined by modern college teams. Whether that will remain the case in the 2020s remains to be seen. Appalachian State at least hasn’t given up on it.

Great read..

Is mid-zone it’s own thing or is it just a variation of wide zone?

What types of offenses were 2019 Ohio State and 2019 Alabama ?

Feel like they used a good amount of wide zone, even from shotgun.

Mid zone is mostly considered its own thing and it’s a common shotgun play. You can recognize mid zone because the OL get more lateral than on inside zone but on the play side they block toward the guard and tackle often end up basically kicking out and riding the DL up the field and the running back cuts back inside of them. It virtually never gets to the perimeter and while the RB aims for the C-gap he’s aiming inside of that tackle more often than not.

Alabama used more outside zone back in the day with guys like Mark Ingram, Mario Cristobal likes that play. Ohio State used it quite a bit last year, a testament to both their line and Dobbins that it worked out pretty well. At least until they faced Clemson.

Daily Bullets (July 2): Mike Gundy is to Stillwater as Mike Leach is to Lubbock - Big 12 Blog Network

[…] Scroll (briefly) until you see orange and black in this article and you can learn all about Cowboy Football’s offensive strategy in a pretty straightforward […]