This should be our final piece to this puzzle and then I’ll begin to move on to the always popular Big 12 class breakdowns. In part I we focused on the ways in which teams still run 3-4 and 4-3 base defenses in the spread era today. These are increasingly less common because of how limited they can be in allowing a defense to draw up coverages to defend a good spread passing attack, particularly the smashmouth spread which creates extreme run-pass conflict that demands more coverage on the field.

The 3-4 is more flexible if the team uses faster space-backers at either OLB spot AND utilize truly versatile coverage defenders at CB and S. The 4-3 is dying a pretty quick death nowadays, I don’t think there are any true 4-3 teams left in the Big 12 now that Glenn Spencer has bene fired from Oklahoma State. The K-State model of 4-2-5 I detailed in part II is winning out across the league even as it struggles in Manhattan.

Today we reach the odd front sub-packages turned base defenses, which are much simpler to explain than the wide varieties of 4-2-5 defenses we see today.

The 3-3-5 defense

Personnel: Three DL, three LBs, two CBs, three Ss

There are a few different types of 3-3-5 defense but the true, original base 3-3-5 is the one that you see every Saturday from West Virginia. The main components to the true 3-3-5 defense are a nose tackle, a pair of DE/DT hybrids, three inside-backer types that can play a few different roles, and then your normal nickel secondary with three safeties.

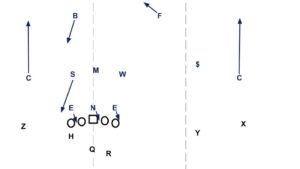

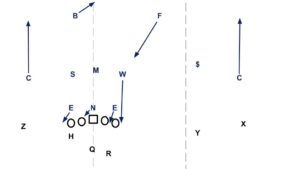

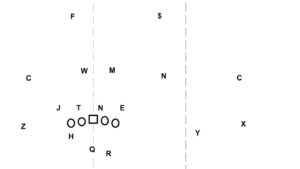

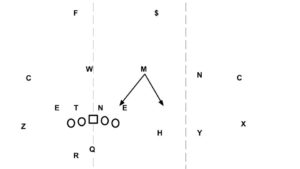

The original 3-3-5 is designed to allow the defense to shift numbers around just before or after the snap to create different fronts and defenses by slanting the DL and moving those three LBs around. West Virginia tends to create really traditional eight-man fronts backed by conservative cover 3 calls out of their 3-3-5 stack look. Such as the Over front:

Or the Under front:

And of course they also may play fronts where play a straight three-man rush and drop eight into coverage (or bring six, seven guys and play very few in coverage).

The true 3-3-5 is a nice scheme for non-blueblood programs because the shifting and multiplicity of it calls more for tweeners and skill players rather than rare athletes that can go out-execute opponents like the 3-technique DT. The design of the true 3-3-5 is to utilize speed and versatility to easily shift numbers around in a disguised fashion in order to outnumber either the run or the pass.

West Virginia typically relies on a three-deep shell while moving around which guys comprise the eight-man front and where they tend to shade in order to address the different concepts or featured players from the offense. Iowa State utilized a similar style with their 3-3-5 this past year but they shifted around between “two-robber” and quarters coverages in order to move numbers around to different spots whereas West Virginia will utilize “2-robber” but they never play quarters.

The 3-3-5 relies pretty heavily on having an athletic nose that can slant into the A-gaps and arrive with enough power or quickness to command a double team. If the nose in a 3-3-5 isn’t commanding a double than the hybrid, shifting LBs behind him can be exposed to getting taken for a ride by an advancing guard.

The San Diego State 3-3-5 is another true version of the system that’s possible even more tweener-oriented than the West Virginia version.

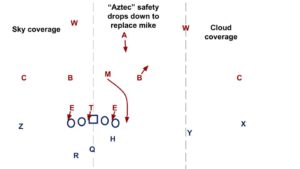

The Aztecs like to use a “four-corner” type approach to choosing their CBs and the “warrior” safeties in order to allow them to play lots of quarters coverage where the warrior safeties are playing vertical routes from the slots with help coming (sometimes late) from their LBs dropping back late into coverage. The “Aztec” safety is a robber player that often ends up dropping down to essentially play the role of a linebacker:

What makes it work for them is that their DL are always 260-pounders that are really well drilled at moving after the snap and playing blocks and opponents rarely have the Aztec accounted for in the blocking scheme so he regularly comes free to make the tackle.

Then there are two other types of 3-3-5 defense that aren’t really the same as the systems I’ve outlined here. First you have the type of 3-3-5 that Oklahoma has dabbled in when they haven’t had Caleb Kelly or Eric Striker on the field and replaced them with a DB.

This is just a standard 3-4 that happens to have a DB as the sam linebacker. As I attempted to explain throughout the 2017 offseason and actual season, when you have a DB out there who can play the edge from space like a linebacker but also hold up in man coverage carrying a receiver down the field it significantly expands the kinds of coverages the defense can play and makes them harder to target with play-calls.

The other type of 3-3-5 defense is really just a 4-2-5 with a hybrid DE/OLB, OU dabbled with that as well this season and probably should have played it more:

Now the defense is playing a “four-down” front, they just happen to have their weak side end positioned to drop out and play linebacker. Being able to drop that hybrid “Jack” LB brings greater flexibility to the defense, particularly in making it easier to disguise coverages or blitzes. If you can find and teach hybrid OLBs rather than pure DEs it tends to offer more options and multiplicity to your pass defense, although some teams prefer to have DEs that focus on playing good run defensive technique.

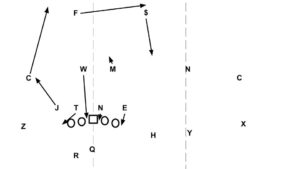

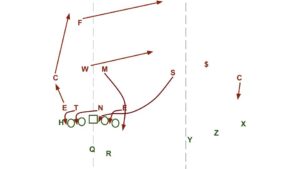

One of the best tactics you can play from this style of 3-4 is to bring a late, A-gap blitz from one of the inside-backers, roll the safeties over, but then play a bracket on that solo-side WR. Oklahoma gave Baylor fits doing this back in 2015 and erasing Corey Coleman from the gameplan.

In this example the strong safety drops down and plays like a middle linebacker would in quarters coverage while the free safety plays over the top in the strong safety’s spot. On the backside you’d think the defense would be vulnerable with that corner isolated on the backside WR but the defense is A) bringing a quick-hitting pressures up the middle and B) dropping an OLB underneath the backside WR and thus allowing the corner to play it more conservatively over the top. This is a pretty nasty call that you see from most every three-down defense.

The 3-2-6 defense

Personnel: Three DL, two LBs, two CBs, four Ss

The 3-2-6 is basically a recognition that the 3-4 isn’t optimal for defending spread offenses and the expansion of a dime package into a base defense. Texas embraced the 3-2-6 last season when it became clear that A) spread offenses didn’t have a great answer for the two-robber coverage and B) Texas was better as an all around defense by playing more versatile athletes (i.e. four safeties) rather than specialists.

I don’t know when exactly the Katy Tigers embraced the 3-2-6 but their legendary 2015 defense played like a 3-2-6 despite utilizing current West Virginia safety Jovanni Stewart as a de-facto DE and the 6-5, 222 pound LB Hunter Stinson as a hybrid LB/safety.

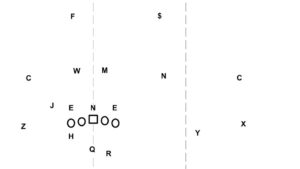

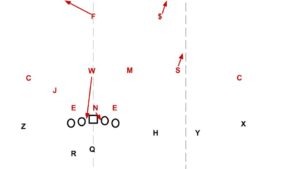

The Tigers evidently start by teaching their outside linebackers as safeties before moving (presumably the bigger, stronger ones) them down to the outside LB spots. This gives them a ton of versatility that I’ll detail here just in how they can handle the dreaded trips formation:

In this call they bring the weak inside-backer up the A-gap, preferably late and disguised, and drop the free safety into cover 2 on the boundary while playing some brand of quarters coverage to the field. Between the nose, WILB, and two DEs the defense is filling all four interior gaps and spilling the ball outside to the middle LB and the two S/LB hybrids I’ve labelled as “S” and “J.”

In this call they drop that jack safety deep into cover 2, play cover 2 on the opposite end, and roll the free safety into the “2-robber” role where he’s a free hitter against the run.

The three DL and two inside-backers account for the interior gaps and can easily adjust to any pullers or motion and then that free safety is typically playing downhill and wrecking everything from the robber alignment. It’s essentially the same as an old Tampa-2 defense except the middle linebacker starts the play deep and can come downhill from there. You’re going to be seeing a lot more of this, especially given how successful it was for Texas and Iowa State last season. That robber is a devastating weapon against spread run games which haven’t yet adapted to account for him.

So you can tell that the design of the 3-2-6 is a tad different than the 3-4 even though it often has the same structure, the goal here is more about plugging the interior and spilling the ball to speedy players on the perimeter. It’s also more about having matchup and coverage flexibility in a fashion similar to the 3-3-5 but with an even greater emphasis on using flexible athletes.

Like the other three-down fronts, the 3-2-6 relies heavily on having a really good nose tackle that can control the A-gaps and command and resist a double team. Without that, it unravels. Additionally, it’s finest deployment will come from having versatile and sturdy safeties in the outside LB positions. The 3-2-6 is basically a defense for teams that get amazing nickel play and then ask, “how can we get more out of these guys?” It’ll probably be a mainstay for Texas in the coming years, especially after this 2018 recruiting class that included six top rated DBs, one of whom is 6-4, 200 and born to play a hybrid role.

The 4-1-6 defense

Personnel: Four DL, on LB, two CBs, four Ss

This is just taking the 4-2-5 to its logical extreme against spread offenses that continue to push the envelope with four and five receiver sets. As my man Coach Alexander notes in his breakdowns of the 4-2-5 defense, the middle linebacker is necessarily attacked and put in conflict on the reg.

As I’ve noted repeatedly of the K-State defense that served as an inspiration for his defense, even the Under front adjustments to move the B-gap still ask that one of the LBs be able to cover a lot of lateral distance to handle both his coverage assignment and the inside run fit.

There’s a dozen ways to help that guy out that teams will employ. K-State will often mix in single-high safety coverages where the strong safety spins down and covers that “H” receiver so the LB can stay in the box and they’ll also have that DE play a “heavy” technique and try to either dart into the B-gap or squeeze it closed by shoving the tackle inside. I noted in part I that North Dakota State will often use stunts to close that gap or else drop that free safety down to replace him in the box.

The only issue with all of that is that you are having to apply band-aids to your base defense to make it sound and workable against a really simple and multiple base offensive formation. The easier solution is to have a guy there with the lateral range to do more.

TCU was halfway embracing that solution with Travin Howard, Kansas State usually plays their most athletic LB there (Arthur Brown, Elijah Lee, Jayd Kirby, etc), but Matt Rhule found what might be a better solution up in Temple. That was the 4-1-6.

Rhule’s defense is built out of the old Joe Paterno Penn State 4-3 defenses that utilized the Over and Under front as well as the zone-blitz, tending to rely more on the Under backed by cover 3. Like the old 4-3 Under his system is designed to direct the ball to a rangy weak side linebacker who then cleans everything up. When he had Tyler Matakevich, who was rangy but more of a traditional inside-backer at 6-0, 230 pounds, he’d mix in 4-2 nickel and 3-2-6 dime to keep him on the field. Matakevich had 100+ tackles four years in a row at Temple with 137 in 2013 and 138 in 2015.

In 2016 Rhule didn’t have another Matakevich so he played the 5-11, 205 pound Stephaun Marshall there instead and took advantage of having the skill set of another safety on the field down in the box. His defense always aimed to cover up the weak side linebacker and allow him to run to the ball anyways so playing a 200-pounder there against spread teams wasn’t a big stretch.

Against college offenses that don’t yet make the most of the RB as a hybrid weapon in the passing game, teams are finding that they really only need about five guys in the box that are really sturdy, downhill players and then they can use those guys to take on blocks and spill the ball to speed everywhere else on the field. If your defense is designed to give you a +1 against the run or pass, as most defenses are, then the only way to respond to spread tactics is to field enough speed to allow you to cover the increasing amounts of space to get the +1 defender where he’s needed.

The 4-1-6 is also a nice counter to the 3-2-6 because it can still allow a team with really good, disruptive DL to attack the offense and it doesn’t necessarily need the same kind of dominant nose play (although it does need to force a double somewhere) as the odd fronts. Of course Rhule was also amazing at developing hybrid DEs at Temple so the 2016 defense featured Praise Martin-Oguike and Haason Reddick and regularly dropped them into coverage so that it was arguably more of a 2-3-6 dime defense in terms of personnel.

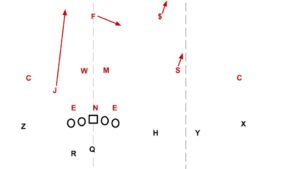

You can see how Rhule took advantage of all that versatility and athleticism in this blitz I drew up from his 2016 dime defense:

Against USF here they lined up in a 4-3 Under with dime personnel. At the snap they dropped Reddick, blitzed the “sam” LB who was more of a nickel, blitzed the middle LB after him, rolled the free safety, and rolled “weak side LB” Stephaun Marshall WIDE to the field to form a two-deep coverage with five pass-rushers.

I also almost forgot to mention the 2009 and 2010 Nebraska defenses that regularly employed a 4-1-6 “peso” package from which they could play a variety of different coverages behind a dominant DL led by Ndamukong Suh and then Jared Crick. Those Ds ruined B12 offenses.

Dime affords so much more versatility to a defense and if the DL is good enough, being able to consistently outnumber opponents means that teams often find that their dime package can hold up against teams using TEs or FBs if their hybrid safeties on the field are physical enough at taking on blockers.

For Big 12 defenses trying to stop the league’s lethal spread offenses and build top units from Texas HS players, dime is increasingly going to be the way they go.

A trend I’ve noticed from a lot of 4-man front HS teams out west has been simply to change up personnel without altering the structure of the defense.

So against more run-centric offense (21 & 12), they’ll come out in a 4-3. Against 11 personnel, they’ll swap the Sam for a nickel player. And against 10 personnel (or 11 with a great receiving tight end), they’ll swap the Will for another defensive back or hybrid player who will align to the #4: the boundary slot vs. 2×2, the inside slot vs 3×1, or the tight end. Keeps everything pretty simple.

What I haven’t seen, and I wonder if it might become a new trend, is to see the same tactic with 3-man front teams. But it should work in principle.

From what I can tell, CenTex power Lake Travis plays a 4-3 but just always leans on light, rangy, but still tough guys at both Sam and Will. So it’s sorta like a dime but it has the structure of a 4-3 and they don’t drop those LBs into the deep middle or anything like that. They’re still LBs, just smaller and faster. That’s more or less what TCU does as well with one of their two LB positions.

It’s interesting that you accurately describe Rhule’s defense as a 4-1-6. He inherited Taylor Young at WILL, a stud in his own right but a unique player. The direction that Rhule goes at WILL and SAM (Clay Johnston a shoe-in at MIKE) this coming year should be really telling.

Baylor was down to it’s final 4 scholarship linebackers by the end of the season, so it was really tough to tell the direction Rhule wanted to go. 2 athletic-LB types redshirted, and one DE/OLB (DeMarco Artis) moved to LB, so there will be plenty of options.

Baylor also played a fair amount of 3-2-6 against the air raid teams, bringing in 2 extra safeties to play outside each ILB. It’s been really interesting watching Rhule adjust to Big XII offenses.

He seems pretty flexible, like he’ll figure out who his players are and choose formations from there.

He has to get good DL play though for any Baylor Ds to resemble the ones he had at temple.

Question pertaining to the WV 3-3-5 stack.

Baylor used a diamond formation with 3 RBs against WVU. When asked about it post-game, Rhule mentioned that it was something they only introduced for this week because of WVU’s front.

I’ve been thinking about this, but I’m not sure what the idea is. My best guesses are: (a) there isn’t as much a point having an in-line TE or H-Back against the 3-3-5 because there is nobody to kick out, reach block, etc. (b) having more speed in the backfield to execute blocks on LBs as opposed to asking heavier TEs to reach them.

The thing I can’t figure out is: Baylor ran a ton of 10 and 11 personnel this year. Specifically, why is a diamond formation better against the 3-3-5 than running 10 personnel? Baylor certainly had a lot of success with the diamond formation.

That’s a great question. My guess would be that WVU’s love of slanting and stunting could put them at risk to an offense that doesn’t present a clear target.

Like, how do you stunt your 3-3-5 into an Under if you don’t know where the strength of the formation will end up being?

That’s just my guess.

Explaining my terminology for B12 positions – Concerning Sports

[…] 12 and the roles that are emerging. I wrote up a glossary for positions a few years back and then for formations more recently. But then my preseason All-B12 team included the “shock trooper” in addition to my […]